Just southwest of the Middletown Friends meetinghouse lies a small burial ground purchased for the interment of African Americans 225 years ago, at a time when almost a third of the county’s black population remained enslaved. There are no headstones or any other visual indicators to distinguish this plot from the rest of the meeting’s shaded lawn, and like other Quaker meetings in the area, Middletown did not begin keeping burial records until after the Civil War. It is therefore unsurprising that this burial ground has been forgotten in the intervening centuries. The current overseer of the cemetery was unaware of its existence, and while a “Negro burying ground” is referred to in the meeting’s property records, I was not able to identify it’s specific location until I discovered the original deed for the land in the archive of the Friends Historical Library.

Throughout the colonial era, burial grounds were places of great social importance to enslaved Africans. For example, in Philadelphia the section of the Strangers’ Burial Ground (now Washington Square Park) that was set aside for blacks drew large crowds on Sundays, holidays, and fair days. During these gatherings the burial ground became an autonomous African cultural space where participants came together to perform African dances and to speak and sing in their native languages. This was not the case in rural Bucks County, where the small scale of slaveholding meant that the enslaved had few opportunities to interact with other Africans. Slaves were permitted to attend the fairs that were held twice each year Bristol, but only on the last day.

Records indicate that early Quaker settlers initially permitted the burial of Africans in their burial ground, but this was quickly curtailed. Middletown Monthly Meeting, located on the western border of Langhorne Borough, set aside a portion of their burial ground for blacks in the early 18th century, but the meeting vacillated with regard to their treatment of the African dead. Middletown Meeting segregated their burial ground in 1703, noting in their minutes, “There having been formerly some Negros Buryed in friends Burying Yard which they are not well satisfied with therefore Robert Heaton & Thomas Stackhouse are ordered to fence off that corner with as much more as they may see convenient, that friends burying place may be of itself from all others.” After the construction of a wall around the burial ground in 1734 the Friends reaffirmed their opposition to sharing their burial ground with African Americans, ultimately declaring in 1739, “this meeting having had the Matter under Consideration it is unanimously agreed that hereafter no Deceased Negros be Buried Within the walls of the graveyard Belonging to this meeting, & Adam Parker, Jonathan Woolston & Joseph Richardson are appointed to keep the keys of the Said Graveyard & take Care that none be Buried therein but such as they in the Meetings Behalf shall allow of.” The black residents of Bucks County would not have a dedicated burial ground again until the Society of Friends changed its stance on slavery in the late 18th century.

The acknowledgement by the Society of Friends that participation in the slave system violated their religious teachings also sparked a broader concern about the economic and spiritual well-being of African Americans. After Philadelphia Yearly Meeting banned slave ownership in 1776, they also added the treatment of free blacks to the list of religious queries that their constituent meetings were expected to address. Bucks County Quakers responded by appointing committees to meet with black families, holding meetings for worship for blacks, and eventually purchasing a small plot of land adjacent to Middletown Meeting as a “Negro burying ground” in 1791. This parcel measured sixteen and a half feet wide by 136 feet long, large enough for perhaps a few dozen burials. While the section allocated for blacks in 1703 was almost certainly meant to be used for the burial of slaves owned by members of the meeting, this small lot was purchased for the use of the free black community.

The meeting did not record the burials in this lot and few details about its use remain. The only documented burial that has been identified at present is that of Cato Adams, a free black man who resided in Middletown for a number of years before moving to Bristol. The will that Adams drafted in 1810 demonstrates the burial ground’s importance to the local black community. Although Adams had a number of children and grandchildren to consider when writing his will, he set aside five pounds “for the purpose of keeping in repair the Burying ground appropriated for the interment of black people near to the meeting.” He also left his “first day clothes” to his son. The use of the Quaker term “first day” rather than “Sunday” indicates that he may have attended meeting for worship at Middletown Meeting, although like most African Americans who worshipped with Quakers in this period he was not a member of the Society and does not appear in the meeting’s records. When Adams died in 1812, Orphans’ Court records related to the settlement of his estate show that his executors paid Isaac Gray, a founding member of the independent black Methodist group the Society of Colored Methodists, to dig his grave. The small lot purchased in 1791 was apparently approaching full capacity by 1816, when Middletown Meeting bought an additional lot for the burial of African Americans at the northeast corner of their property along what is now Green Street. This parcel constitutes the northern half of Mt. Olive Cemetery, which was used by Langhorne’s black community into the 20th century. Before the establishment of Bethlehem African Methodist Episcopal Church in 1817 these burial grounds were the only public spaces in Bucks County to which African Americans could claim a collective right.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

Although evidence is scarce, at least two other African-American burial grounds were created by Quaker meetings in the region. The first was Byberry Preparative Meeting, which established a small African-American burial ground in 1780. This burial ground is now part of Benjamin Rush State Park near the border between Northeast Philadelphia and Bensalem Township, only about four and a half miles away from Middletown Meeting. Joseph C. Martindale provides a brief account of this burial ground in his book A History of the Townships of Byberry and Moreland in Philadelphia (1876):

Previous to this time the colored people who died in the townships were generally buried in the orchards belonging to their masters or in the woods; but forty or fifty had been interred in a kind of cemetery for them, on the lands lately owned by Charles Walmsley. It was located in the field fronting the mansion house, not far from Watson Comly’s line. All traces of it have long since been destroyed, and hundreds have since passed over the spot not knowing that they were treading upon the graves of the long since dead. Another of these graveyards was on the farm lately owned by Mary Hillborn, where several slaves were buried. The exact spot is not now known. Many persons by this time had had their attention drawn to the matter, and efforts were made to secure a proper place for the burial of such people. Accordingly, in this year [1780], we find that Byberry Meeting purchased a lot of Thomas Townsend for a burying place for the blacks, and the practice of burying on private grounds was discontinued. The record says that the first person buried there was “Jim,” a negro belonging to Daniel Walton.

Later, after discussing the local potter’s field where white indigents were interred, he writes:

The graveyard for colored persons… is still kept for that purpose. Some years since a portion of this yard was plowed up, and most of the “little mounds” were leveled with the earth around, so that the exact spot where many of this race were buried can no longer be seen. What a pity that man should ever be willing to disturb the resting-places of the dead in order to add to his coffers! Of late years more care has been taken of this place, and it is now kept in good order by Byberry Meeting.

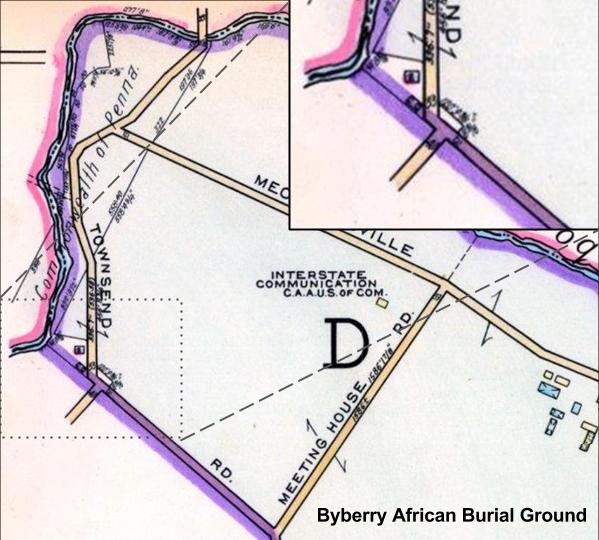

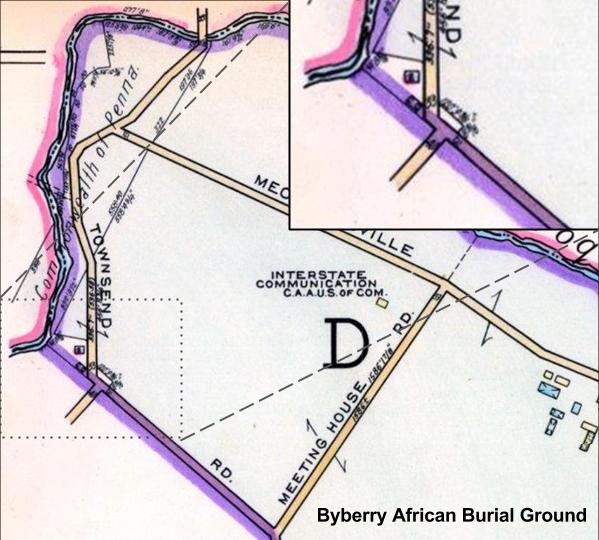

The only historical map that I’ve been able to locate that shows the Byberry African Burial Ground is the “Atlas of Greater Northeast Philadelphia” in Franklin’s Proposed Real Estate Atlases of Philadelphia, Vol. 7 (1953). The small lot is not identified as a burial ground, but the property boundaries are visible:

More detailed maps, photographs, and other documentation are provided in Byberry Librarian Helen File’s paper on the burial ground and an archaeological study of the site performed by the US General Services Administration in 1993.

The second Quaker meeting in the area to establish an African-American burial ground was Buckingham Friends Meeting, which laid out a small section of their existing graveyard for that purpose in 1807. They report in their minutes:

We have laid out a small portion of Ground within the large Grave Yard at Buckingham to Bury Black People in, Beginning at a stone standing at the North Corner of the Old enclosure, thence N 50 [degrees] E two Perches to a Stone, thence N 40 [degrees] W to a Stone standing at the back Wall of the Yard And to be comprehended by these two lines, the Back Wall, and the Foundation of the Old Wall. The Meeting Uniting therewith, directs Burying in rows beginning at the North End…

Unfortunately the exact location of this plot is unclear, but it is probably located in the northwest section of the current burial ground. Further examination of the meeting’s property records may yield a more exact location. While the author of the Buckingham Meeting’s National Register of Historic Places nomination claims that “The African American burials here were made unnecessary within a few years” after Mount Gilead African Methodist Episcopal Church was constructed nearby in 1837, a recent archaeological survey of the site conducted by Meagan Ratini suggests that the burials may not have taken place there until the 1860s. If that is the case, the African-American burial ground at Buckingham Meeting may have been in use for half a century.