Above: Princess Ladybug (1930) – Now in vaults of the Library of Congress

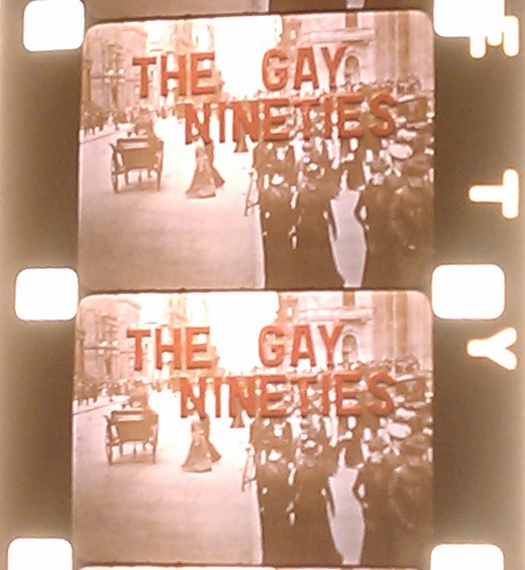

From the dawn of the film era in 1889 until 1951, the 35mm films projected in movie theaters were printed on highly flammable nitrate film stock. In addition to being hazardous nitrate decomposes, producing caustic gas that builds up between the layers of film. It also shrinks, eventually causing the emulsion to separate from the base, and in the later stages becomes sticky until the layers of meld into one black disc, ultimately crumbling into a rust-colored flammable powder. If stored improperly, nitrate film can even spontaneously combust. All of these properties pose significant problems to the archivists tasked with preserving film.

While preserving nitrate is difficult, it is also extremely important. It has been estimated that 90% of films from the Silent Era and half of all sound films made before before 1952 are lost forever.

Film preservationists have determined that the best way to store nitrate is to place it in a climate-controlled vault that keeps the film cool, dry, and well ventilated. Of course the storage area must also be built with fire safety as a high priority. As a result, there are few facilities that can safely deal with nitrate. The British Film Institute converted a nuclear bunker to store their nitrate. In the US, there are a few facilities. UCLA has a vault in Santa Clarita, and the MoMA has a facility in Hamlin, PA. One of the largest and best run nitrate facilities in the world is run by the Library of Congress (LOC) in Culpeper, VA, in a former Federal Reserve bunker.

I’m friends with a local film preservationist who has donated hundreds of films to the LOC over the last few decades, ranging from the hallowed work of Edison and George Méliès to campy sci-fi and westerns. He has also periodically lent out films for restoration projects, including Disney’s restoration of Fantasia. In 2009 I helped him coordinate the donation of about 200 nitrate items to the LOC, which constituted the vast majority of his remaining nitrate collection. For the next few years I gently encouraged him to give the LOC his few remaining prints, but he wanted to hold onto them.

Bare Knees (1928) – A flappers era comedy donated to the Library of Congress in 2009.

I finally found my chance this spring. He read in the Vitaphone Project newsletter that the soundtrack to his print of Princess Ladybug (1930) had been found in Australia. The film was from the early sound era, before soundtracks were printed on the film itself. Instead, the sound was recorded on shellac records that were played in sync with the film using a Vitaphone player. As a result, you need both the records and the film print in order to reproduce the movie in its entirety. Because the image and the sound are so easily separated, many of the Vitaphone movies that still exist survive only partially. A film print may be sitting safely in an archive but the sound has been lost, or vice versa.

The discovery of Princess Ladybug’s soundtrack was the impetus he needed to make another donation. He wanted to send Princess Ladybug to the LOC to have it reunified with its soundtrack for the first time in over 80 years, and was willing to add a number of other prints as well. I put him in touch with the Nitrate Vault Manager, and volunteered to drive the films down to Virginia for him.

Below are the pictures of my trip:

Packed to the gills with nitrocellulose. Highlights include Charlie Chaplin’s Work (1915), a mint fox newsreel showing Mussolini being hanged, the color segment from the first film to feature the three-strip Technicolor, Princess Ladybug (1930), a Vitaphone short whose audio was recently discovered, shot in the extremely rare Photocolor process, and the only existing print of Popeye Meets Sinbad, also Technicolor.

Formerly used as a Federal Reserve building, they got rid of the machine gun nest and traded the gold for silver halides. George the Nitrate Vault Manager wheels the film in through the front door.

Authorized personnel… but a little ragged after the 5 hour drive.

The lab just outside the nitrate vault. The reel being examined is a from Cinerama film. The Cinerama process created a super wide image by projecting three side-by-side images at once.

This is where nitrate is brought for preliminary examination. It’s also where researchers are allowed to examine nitrate prints. The vacuum cleaner (back center) is explosion proof. The blue barrel is where they dump nitrate that is beyond repair. They pour water over it and reseal the container. He cracked the lid to show me… nasty chemical slurry.

Inside the vault!

The major studio’s prints are stored in banks of consecutive storage rooms.

George explains how sheets of water pour down to contain a fire.

The shelving is designed so that if one reel ignites the fire is contained on that shelf, and the only other reel in danger is the single other reel on that shelf. The film cans are waterproof but air permeable, allowing the nitrate to off-gas. The room is ventilated so that the atmosphere in each room is completely replaced every half hour or so. It’s also cold. The nitrate is stored at 35 degrees Fahrenheit, with a 55 degree acclimatization room. Any time a reel enters or leaves the vault, it’s brought to the acclimatization room for one day. By changing the temperature in stages, they avoid letting condensation form on the film.

Waterlines hang above the shelves, and the lights are completely sealed to prevent an electric shock from igniting the film.

Devil’s Playground taunts us with the potential hellfire of a nitrate eruption.

Unknown Circa 1904 Romance

“Here’s the one that started it all!” — The original camera negative for The Great Train Robbery (1903).

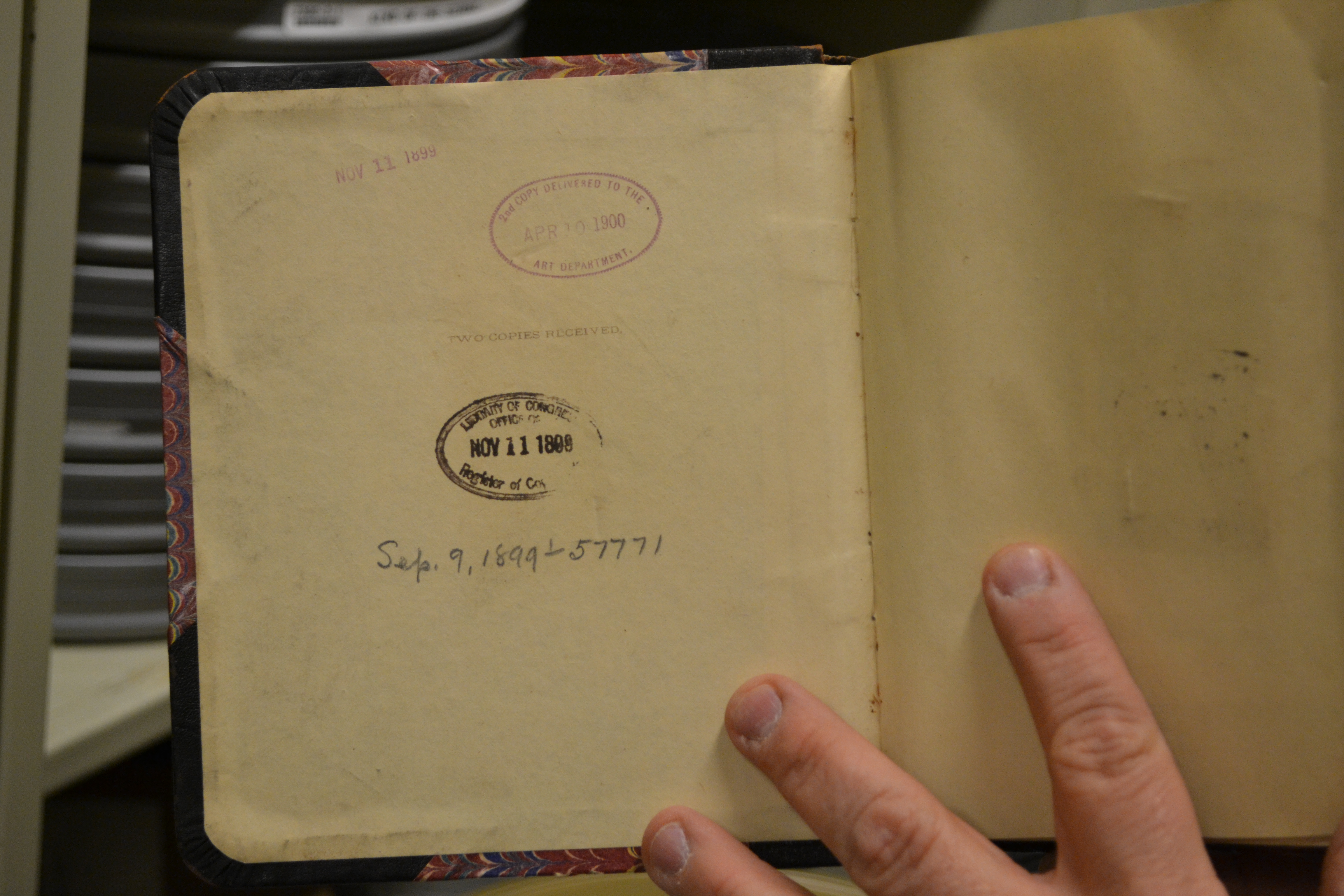

Copyright submission for a film reproduction of an 1899 boxing match.

September 9th, 1899.

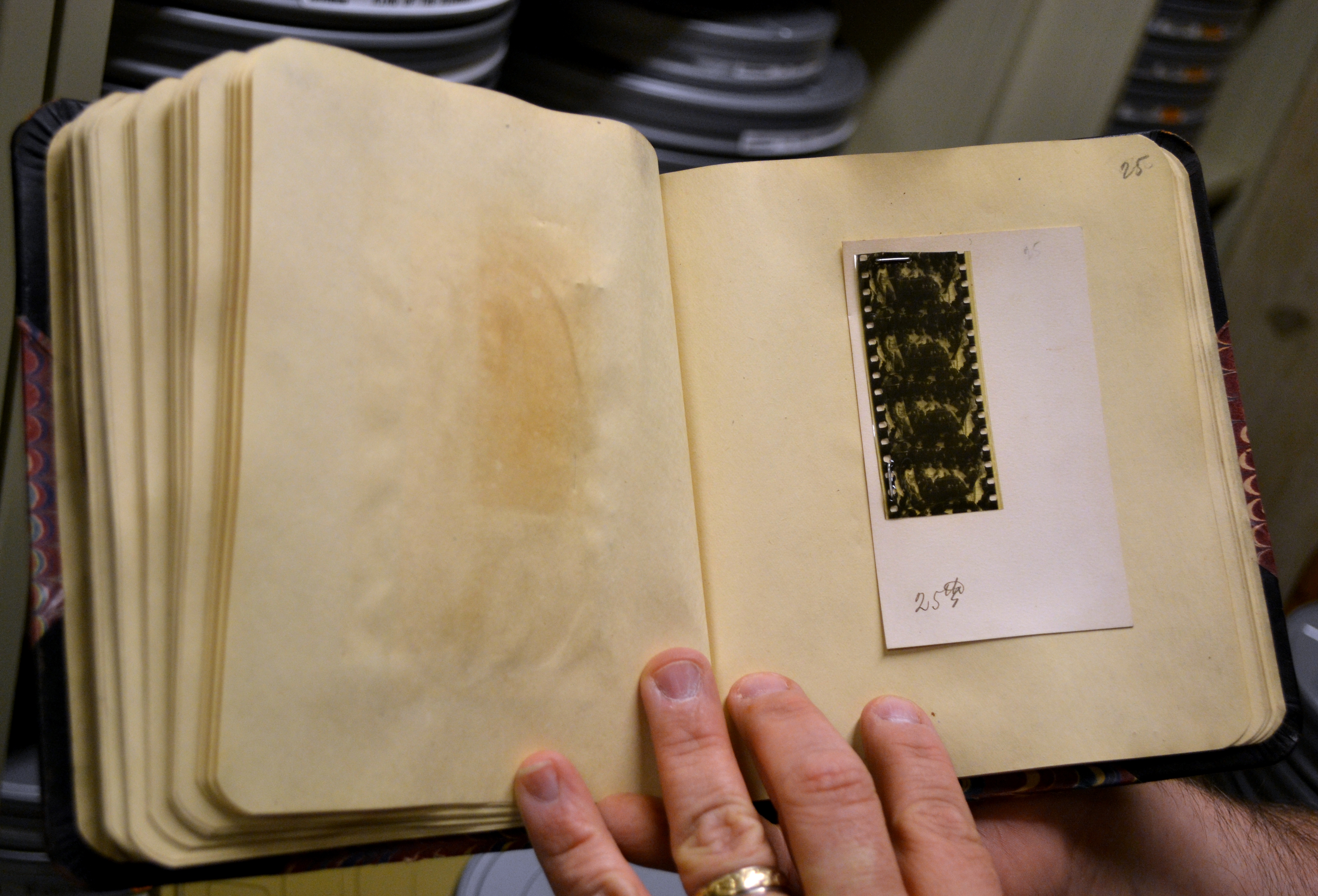

Copyright law didn’t specify rules for moving images, so filmmakers sent in four frames from each scene to copyright them as still images.

They made it to the 25th round. Looking pretty good for 114 years old.

A nitrocellulose film base was used to a lesser extent for still photography. The nitrate negatives for a lot of the iconic photographs from the Great Depression are stored in this room.

“This one almost killed me!” – When George picked up this can, the decomposing nitrate was off-gassing so badly that he had to open all the windows of his car because the fumes were so noxious.

Best office decorations ever.

They have the best toys.

Edison’s Home Kinetoscope (1912), the first home projection system. The lamp housing has been removed to show the carbon arc. Each 22mm reel contained three sets of exposures. It was equipped with two lenses and three side-by-side apertures. You would crank the reel forward, backward, and forward again to play through all the images.

A 9.5mm Pathescope projector. The perforations are between each frame instead of running along the side.

A newsreel camera with a telephoto lens.

The tall unit is an amplifier for Vitaphone, the first commercially viable sound process for film. Look at the size of those tubes!

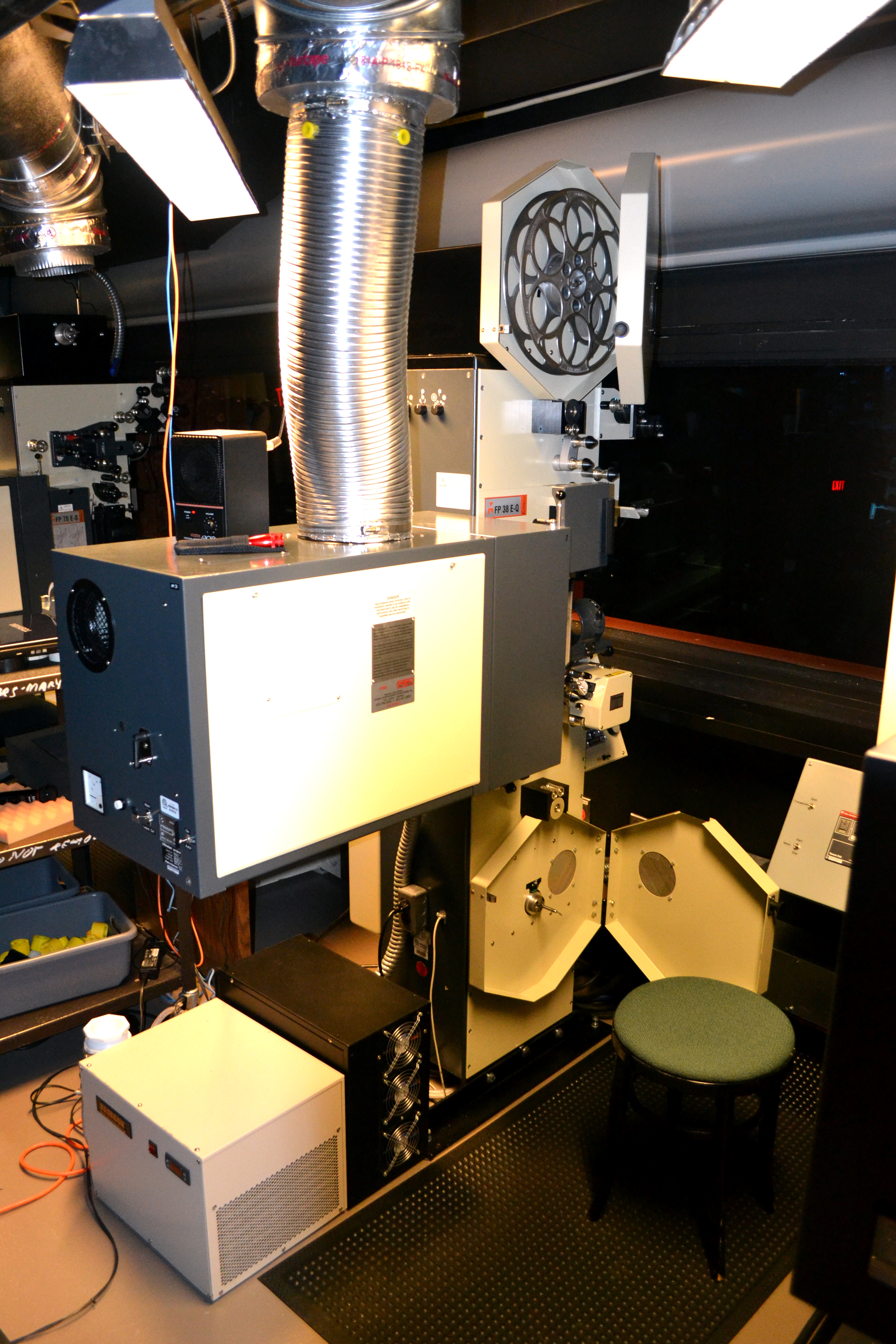

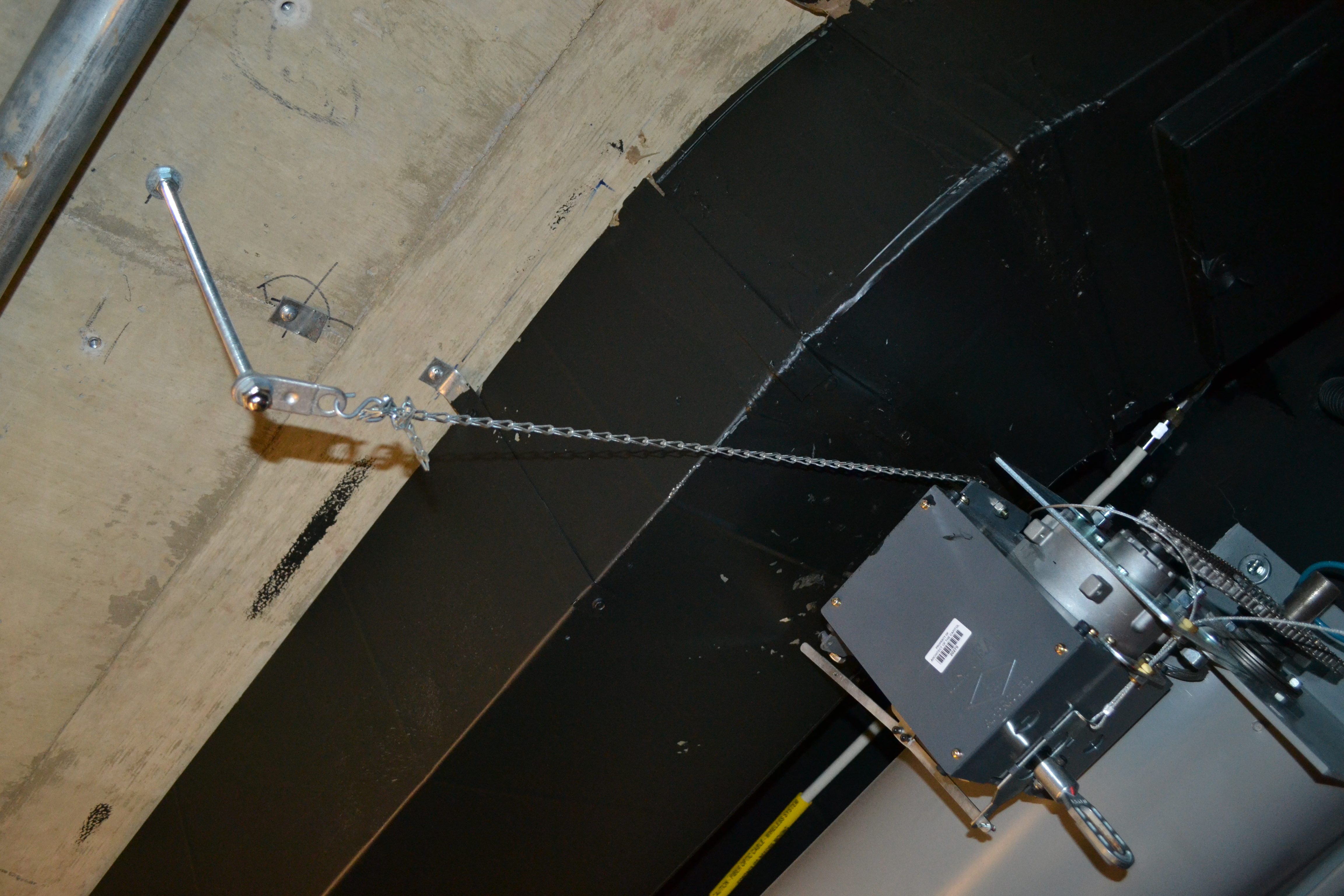

Their projection booth was built by Cardinal Sound & Motion Picture Systems, Inc. to safely project nitrate film. Safety features include enclosed magazines and fire rollers designed to snuff out a flame before it enters the magazines. Unfortunately, the still don’t have any projectionists trained to run nitrate.

A fire activated linkage that closes off the booth in case of a fire. The linkage is made of a metal with a low melting point, so if a fire breaks out it will melt and the chain will drop, lowering a shield between the booth and the theater. Probably one of the only one of these still functioning in the world.

To give you an idea of how dangerous nitrate is, here’s a video of a single reel (about 20 minutes worth) going up in flames. You can jump to 3:45 to go straight to the fireworks:

Of course, this is film that has been purposefully set of fire. Nitrate was the standard for film presentation for more than half a century, and while projectionists had to be far more careful, accidental fires weren’t that common.

To see more beautiful nitrate, check out the Nitrate Interest Group on Flickr.

A few years ago I found a reel of 16mm film on the shelf at the County Theater. It contained a silent film of miscellaneous Bucks County scenery, and wasn’t that interesting. However, enclosed with that reel I found a page of notes referring to another 16mm film shot during Doylestown’s 1938 centennial parade (marking the incorporation of the Borough in 1838). With big plans underway to mark Doylestown’s 2012 bicentennial (commemorating when Doylestown became the county seat in 1812), I decided to track down the missing reel.

A few years ago I found a reel of 16mm film on the shelf at the County Theater. It contained a silent film of miscellaneous Bucks County scenery, and wasn’t that interesting. However, enclosed with that reel I found a page of notes referring to another 16mm film shot during Doylestown’s 1938 centennial parade (marking the incorporation of the Borough in 1838). With big plans underway to mark Doylestown’s 2012 bicentennial (commemorating when Doylestown became the county seat in 1812), I decided to track down the missing reel.