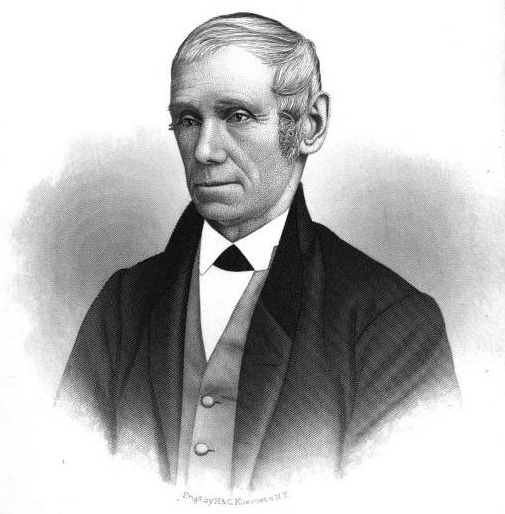

Charles Kirk (1800-1890)

In 1816, the Northern Hemisphere experienced a summer so cold that lakes and waterways were frozen in parts of Pennsylvania in July and August and frost was reported as far south as Virginia. Crops were destroyed by frost at the peak of the growing season, leading to widespread food shortages. In Ireland, the famine was compounded by an outbreak of epidemic typhus, a lice-borne illness that is more prevalent in colder weather because lice can hide more easily within multiple layers of clothing. Scientists now believe the world was experiencing a volcanic winter caused by the eruption of Mount Tambora in Indonesia, the largest eruption in 1,300 years. This disastrous year was called the Year Without A Summer.

The experience of one Bucks County resident serves as a microcosm of this global disaster. In 1879, Charles Kirk (1800-1890) of Warminster composed a series of autobiographical reflections, beginning with his childhood in Abington. One of the first stories he recounts is that of his family’s struggle during the Year Without A Summer. Frost struck throughout the summer months, and like so many other farmers they were left without a harvest. In October his family suffered an outbreak of typhus, which claimed the life of his mother Rebecca and his sister Ruth and afflicted all of the other children besides Charles. His father was already physically disabled due to prior injuries, so at the age of fifteen Charles was forced to assume a heavy burden for his family. He recalls:

The year 1816 was a very eventful year to our family for it was the coldest summer ever in the County, frost in every month. I remember well of seeing in the Sixth Month, of the leaves on the hickory trees dead and crisp by the effects of it. Crops very light indeed. Scarcely any corn came to maturity, enough for to be fit for seed. For several years before and after this time owing to the poverty of the farm we were nearly always out of hay before the grass was cut to turn out a pasture, and out of grain before the next crop came to maturity. These things used to nick me to the very quick, for I was so ashamed to be seen hauling hay in the spring of the year to feed our stock that I disliked to meet anyone for it seemed to manifest to my mind a want of industry and management, but I have lived to see that even this kind of schooling, hard as it was to bear, has had its good effects on my mind.

I now come to the most sorrowful period of my life. In the latter part of the summer of this year my dear Mother was taken sick with what was then called typhus fever, and after about nine days suffering her trials, hardships and her anxieties came to a close in this world and I fully believe she entered into a state of happiness in the next. But here I must pause, for I have no words to convey the feelings of my mind on that occasion, for although more than sixty-two years has passed since that event, still the remembrance of it is clear and strong, so much so that I scarcely refrain from shedding tears whilst writing these lines. There was ten children of us at the time, the youngest about five years of age.

The time of my Mother’s sickness was an anxious one to all the family for she was indeed the head of it in every sense of the word. The fever at that time was thought to be contagious so us children were not allowed to go in the room where she was, but there was a crack in the board partition in the garret stairway that I used to go and peer through to see her. These are the last sights I ever had of her in this life. One day during her illness when out in the field reflecting on the prospect of things the impression on my mind was that if she should die there would be no pleasure left for me in this world, but I had not then learned to look to a higher Power for peace and happiness, the great fountain and source of all good, the sure foundation to build upon in this life.

It was indeed a house of affliction. Sister Ruth took the fever and was dangerously ill for a long time so much so that we were called in more than once to see her die, but after a long and tedious time she recovered. Sister Elizabeth, a girl about twelve years old, sickened and died with it in the 18th of 10th Month, 1816. The rest of the children all took the fever, eight of them sick in bed at one time. I was the only one that escaped and I well remember feeling so thankful for the favor. The neighbors became alarmed, some were afraid to come amongst it but still there were some who rendered every assistance in their power. As I was the only one able to go, there was much that fell to my lot to do at that time. The doctors depended almost entirely on stimulants, wine and brandy was used in large quantities, and I had also to go round and to solicit persons to come and set up with the sick, and even this was a lesson of instruction to me and I have endeavored to profit by it. Never when any of the neighbors were sick not to be sent for but to go and see if I could be of any use.

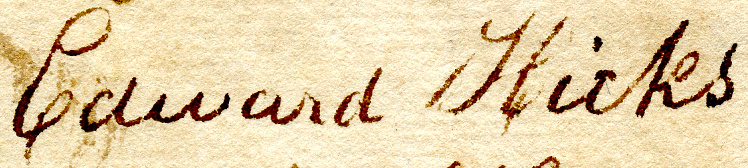

Source: Charles Kirk’s Journal (handwritten copy), Bound Manuscript Collection, BM-B-243, Mercer Museum Library, Doylestown, PA.

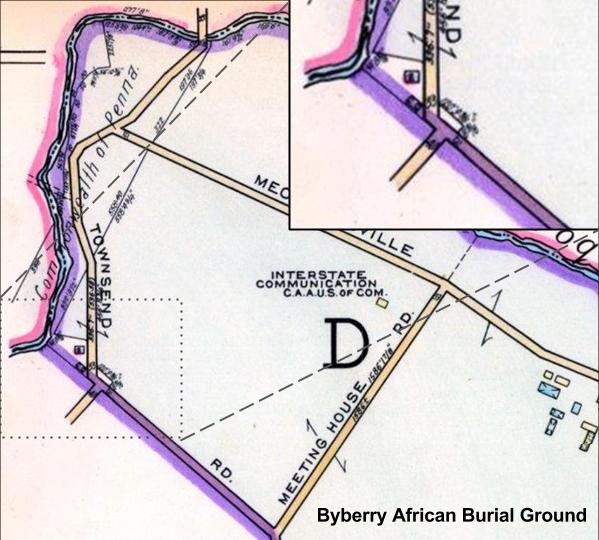

Although the Kirk family continued to face financial difficulty in the years that followed, Charles eventually became a successful farmer. In about 1841 he purchased a 118-acre farm in Warminster Township, and the 1870 US Census values his combined real estate and personal estate at $18,500. He became a respected elder in the Society of Friends, and he participated in the Underground Railroad, sheltering a fugitive from Virginia named Sarah Lewis for more than a decade after slave hunters captured the rest of her family in Philadelphia. Although little trace of his farm remains, having been purchased by the US Navy as part of the Johnsville Naval Air Development Center in 1994, Kirk Road still bears his name. A house that was once part of Kirk’s farm is still standing, currently the home of Gilda’s Club Delaware Valley, a cancer support group. According to the Pennsylvania Historic and Museum Commission, the structure dates to 1817, so it very well may have been the house where Charles Kirk composed his memoires.

Note: The portion of Charles Kirk’s diary excerpted above has been edited for readability. Punctuation has been added for clarity, capitalization has been normalized, and minor spelling errors and slips of the pen have been corrected.

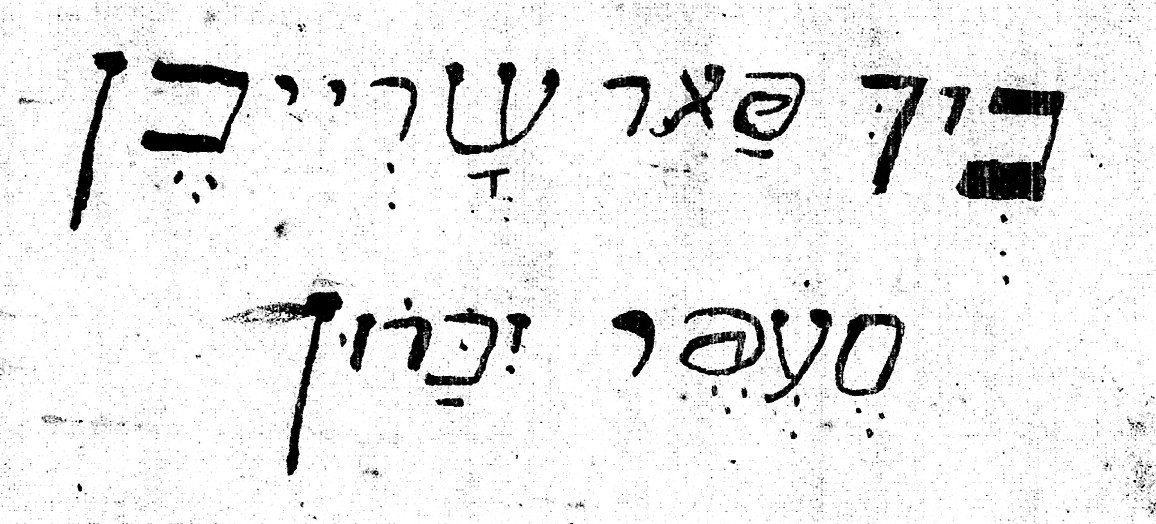

The version of Kirk’s narrative found in the Mercer Museum Library’s manuscript is apparently a transcription of the original text. The book was first used as a record book for public vendues held in Newportville, Bristol Township, in 1841. It was repurposed by a later owner to record genealogical information about the Kirk family and to transcribe the journal of Charles Kirk. This later section is composed in two unique hands, indicating that one person began transcribing Kirk’s journal and a second person completed it. The section excerpted above includes the work of both authors.