In the fall of 1897, prominent Solebury resident Eastburn Reeder, then an old man, was asked to recount his experience at the Solebury Friends’ school to the current generation of students. Reeder started school there in 1836, the first year it was open.

Solebury Meeting has since converted the school building into a residence for their caretakers, which just so happens to be the house I grew up in. The building was heavily altered long before I got there, but evidence of the original open floor plan can be seen in the uneven room sizes and odd layout. Other evidence of its prior use can be found in the old outhouse, where four wooden seats indicate that it was built for a well-trafficked public facility. Now used as a shed, the outhouse also once served as rabbit hutch for a previous caretaker, a serious alcoholic so poor that he had to raise rabbits for meat.

The following is his address, as recorded in the Daily Intelligencer, October 9th, 1897, which I’ve transcribed from microfilm:

In Days Gone By.

———————————————————————————————–

Recollections of the Solebury School from 1836 to 1846.

———————————————————————————————–

A Paper Read at the Closing Exercises of Solebury First Day School

by Eastburn Reader, 10th Month 3d, 1897—A Story of Two Boys.

———————————————————————————————–

A few weeks ago I was asked to give this First-day school my recollections of Solebury meeting of Friends of sixty and fifty years ago. Since that time these words have been continually coming to my mind—“How dear to my heart are the scenes of my childhood.” Whether they were suggested by the effort to turn my mind backward to the day of my youth, or whether they are to be regarded as an evidence of approaching age, I will not stop now to inquire. I have not been able to rid myself of that thought. Like the ghost of Banquo in the story of Macbeth, “it would not down ;” it would not leave me. I am asked to-day to give my recollections of Solebury school, its teachers, and the scholars attending it, from 1836 to 1846, a period of ten years, and all of it more than fifty years, and some of it more than sixty years ago.

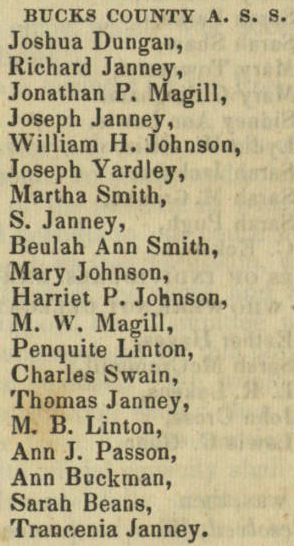

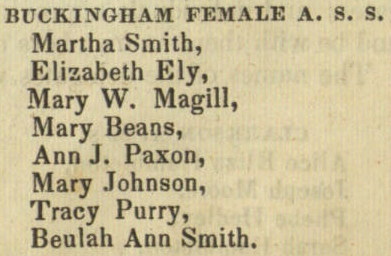

We, (my sister and I) began going to school here in the spring of 1836. I was nearly eight years of age, and my sister a little over five. Our mother went with us the first day, and we all walked to the school house. Whether mother went with us on that day to assist in carrying our books, and dinner, or to tell the teacher who we were, or to protect us from imaginary danger along the road, I never knew. After the school opened, mother walked home, and that was the only time that I ever recollect being taken to or from school. After that we had to rough it, like the rest of the scholars, having no protection from the storms, except an umbrella, or an occasional cloak or shawl. Elizabeth Ely was the teacher that summer, and continued to teach the school for four or five summers after that time, being succeeded by Annie Martin and Sarah Murphy in summer, and by Moses E. Blackburn, Albert Pearson, Charles Murphy, and Edward A. Magill in the winters.

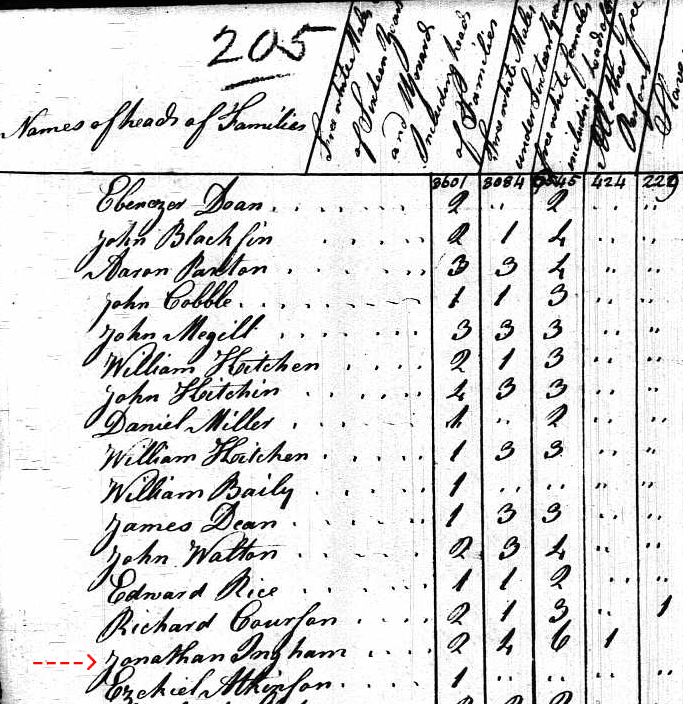

Solebury township had not then (1836) accepted free school law, and our tuition was paid for by our parents at the rate of three cents per day. The teachers made out the bills regularly at the end of each month, which we carried home to our parents. The school was a large one, and the house was crowded to its fullest capacity. It was so large that our teacher had to employ her sister, Sarah Ely, to assist her in hearing some of the classes. The desks were arranged around the walls of the room, the boys occupying one side of the house, and the girls the other side, while a few benches in the centre of the room were occupied by the small children, and by those who did not need desks, having neither books, slates, pens or pencils, but recited their letters etc., at the teacher’s desk. I have a list of over seventy-five names of children whom I can recall to mind as having attended that school during the period that I attended it. These companions of my youth, where are they now? How many are yet living? How many deceased? And how far and widely have they been scattered? I have undertaken the task of ascertaining these points, and although the task is far from being completed I have good reasons for believing that a majority of them are still living. Out of a list of 76 names, 32 are know to be deceased, and 44 are believed to be now living. This, I think, is a remarkable showing for health and longevity—44 out of 76 beings is over 60 per cent. living, and all of them now over 50 years, and many of them over 60 years of age. During this entire period of ten years, we were called upon but once to note the death of but a single one of our school mates, and that was a little boy between 5 and 6 years of age.

The dead, where are they? Of the 32 who are known to be deceased 12 of them have been buried in these grounds. They lived out their allotted lives in this vicinity and have been gathered in with their fathers. Of the other 20, fifteen of them lie in cemeteries in different parts of this State ; three in New Jersey, one in Ohio and one in Bombay, in far away India. The 44 living are believed to be now scattered almost, if not quite, as widely, only five or six of us left remaining within a reasonable walking distance of the school.

It is my object to ascertain the date of birth of all, the date of marriage, of those who married, and to whom married, the present whereabouts and address of those who are living ; and the date of death of those who have died, and the place where they are buried. I am aware that to accomplish this will be no easy task. It will take time, and I may find cases where it will be impossible to gain information I desire. I have already, in the very threshhold of the work, met with some very pleasant and encouraging experiences, and I have also met with some very sad and discouraging experiences. After I left Solebury school in 1846, I was away from this neighborhood most of the time for nearly three years. When I returned in the spring of 1849, and looked around for my former companions, what did I find? I found several of them married, and obeying that command which God gave to Noah in Genesis 8 : 16-17. Others had gone I knew not whether. To ascertain this as far as possible is my object, and while I am waiting for the returns to come in, I will tell the children a story of my recollections of my school boy days.

A STORY OF A BOY

I will tell a story of a boy, or rather a story of two boys. Almost every boy who goes to school, has his chum. This must be natural among boys, or so many of them would not do so. I had my chum. He was one year older than I. He was a boy very peculiar in disposition, and seemed to have the power of moulding me to his will. Everything he said or did, to my mind, was exactly right. Our desks and seats were side by side. This is not only for one term of the school, but it lasted as long as we both attended this school. To secure this end on the last day of a term of school we would each of us leave a book in our desks, in order to secure possession of them for the next term. In these books he taught me to write these lines—

“Steal not this book my honest friend,

For fear the gallows will be your end.”

These lines were signed by our respective names and were supposed to be potent against depredations. We had full faith in this, and our books were never stolen. I have said that my chum had a peculiar disposition. He was inclined to be a rover—he was going to be a sailor, to be a captain of a ship. He said I should be a farmer and have a large plantation. I was to produce articles for him to carry in his ship to other countries of the world. Every day as we studied our geography together afforded him an excellent opportunity to mature his plans. He located my plantation on the Atlantic coast somewhere between Charleston and Savannah. With a stroke of pen and ink he converted a promontory or cape to an island.

This is necessary, he said, so that he could approach my plantation from every side. I was to raise rice and cotton for him to export. To enable me to do this it would be necessary for me to have large numbers of slaves, which he would go to Africa for and capture and bring to me. I will say just here, that our teacher was his aunt, and boarded in his father’s family. She was a very strong anti-slavery woman, and often spoke to us of the sinfulness of slavery and the wrongs of the poor slaves. Whether it was to be in oppostion to the views of his aunt and teacher, that he decided to make a slave holder of me, I never knew. I was to be married, he said, and have a family, but he was to be a sea captain, and they never married or had families. His stories of adventure were so captivating that I believed everything he told me. As I was to marry and live on a plantation and have a family, I began to think about a wife early in life. Every day, instead of studying our lessons in geography, he would say to me “Let us transact business.” That is to say, he would buy up what I had produced for export, and bring back to me any product of the earth that I might desire. This gave us knowledge of geography, in a measure, but it did not give us very often much knowledge of the lesson for the day. Very frequently were the orders given to us by the teacher, “Boys, you must get this lesson over after school.” Then we would put ourselves down to work and soon master the lesson.

I recollect one day in particular as we opened our atlas, my chum told me that he had on board for me a large number of very valuable Araibian horses, fresh from the desert, that he had, with great difficulty, secured for me. He said his ship was now in sight of land, and would soon be in the harbor. He then put up both hands to his mouth to blow the trumpet announcing the arrival of his vessel. He blew louder than he know, for the noise of the blast attracted the attention of the teacher and the entire school. We were ordered to the teacher’s desk at once. Which of us had made that noise? Neither of us would tell. Then both must be punished, and that severely. The teacher had a small chestnut sprout in her desk, from which the bark had been peeled, and it had become very dry and brittle. My chum held out his hand to receive the punishment first, and after receiving a few sharp cuts, he cried out lustily, or pretended to do so, and was sent to his seat with his face deeply buried in his hands upon the top of his desk. It was my turn next, and as I did not cry, for in boy parlance, “it didn’t hurt a bit,” the teacher naturally looked to see why the punishment had not the same effect on me. Her eyes were small, black and fiery, and her expression almost convulsed me with laughter. The blows upon my hand were renewed with redoubled force. At every blow, two or three inches of the switch flew off the end, and it was speedily used up. The boy was still rebellious and defiant. The teacher was too conscientious to use a ruler, but something more must be done.

Accordingly, I was led by the shoulder over to the girls’ side of the schoolroom, where “room was made” for me on the bench between two of the oldest and largest girls in the school. I suppose they were 18 or 20 years of age. They appeared to me then as mountains of flesh, both being large and fat. I was not placed opposite to a window where I could look out, and had nothing but white wall to gaze upon. I could not even see the girl on the other side of the two between whom I was placed. I could not see over or around them, and was almost buried from sight. Had I been placed between two other girls, whom I could name, and nearer my own age, I should have liked it far better. I was compelled to remain there until school closed for the day. When the school was dismissed I was told to remain. The teacher busied herself with mending our goose quill pens, and setting the copies for the next day, until all the scholars had time to reach their homes. I wondered what was to be done with me next. The teacher told me that she had made up her mind to write a note and send it by me to my parents, telling them to keep me home from the school. I promptly told her she could send no such note home by me. Then she would send it by my sister, who would not go home without her brother. I said my sister should not take the note either. I do not know whether it was the tears of my sister, or what it was, but the teacher all at once took a sudden change. She began to talk to me. She told me what a great interest she had felt in me, and what pains she had taken, and how hard she had tried to do her duty by me. And as she talked on in this strain, her tears began to flow as rapidly as her words. This overcame me entirely. I could stand punishment, and scolding, but entreaties and tears I could not stand. I yielded, and promised obedience for the future. The note home was neither written nor sent. As I look back upon this little incident after an interval of sixty years, I can but look upon it as a victory for us both. It was a victory for the teacher, most certainly, for the boy not only promised, but gave obedience. It was a victory for the boy over himself, and it was not necessary to punish him afterward, and he continued to go to that teacher for several summers. She was a faithful, conscientious teacher, and tried hard to do her duty by us. She afterward removed form Solebury to Philadelphia, where she died many years ago, and was buried in Friends’ burial ground at Fair Hill. I intend some day to visit her grave as a deserving tribute to her memory

I cannot close this little story without telling what afterwards became of my chum. After he left school he studied medicine, and graduated with high honors. I believe he was soon appointed a ship surgeon, which was an object of his ambition. In the year 1851 he was appointed by the President of the United States Counsel to Bombay. He remained there for seven years, dying there in 1858. A short time before his death he married, and as they were making arrangements for their wedding trip home to visit his parents his wife was taken sick with some fatal disease peculiar to that country, and soon died. He was also smitten with the same disease, and died. When the news of their deaths reached this country I went to see his parents and sympathize with them in their great affliction. They told me it would be impossible for their bodies even to be brought here for burial. The distance was so great and the nature of the disease such as to render it impossible. I do not even know the name or nationality of his wife, and I may never be able to ascertain it. But I shall never forget the sorrow that was depicted upon that mother’s countenance as she told me the sad story. She had followed to the grave all the rest of her children in early life save one. This was her first-born and favorite son, and those lines of deep sorrow were never entirely obliterated from her countenance, and she lived for many years.

I hope there will be seen in this simple story a lesson for young boys and girls of this , our First-day school. That lesson is—get mementos, or keepsakes of some kind from your teachers and from your most intimate friends. You have far greater facilities to do this than we scholars had sixty years ago. Then photographs were unknown. I have not a single picture of one of my schoolmates or teachers. You can get them now at a very small cost. If you cannot get these, then get a few lines from a favorite author, written in their own handwriting, and signed by their names and date. And more than all, do not suffer yourselves to lose all knowledge of their address. Then no matter how widely the companions of your youthful days may become scattered in this wide world of ours, you will know and feel that you have the power of reaching them, and of communicating with them in a few days at most. It will be a source of great gratification to you when you grow to be old. I have here a card in my hand, a little red card, which I received from my first teacher more than sixty years ago. It was my first card, and is dated 8th mo. 7Th, 1835. I was not then seven years old, I have kept it to this day, and every year it grows more precious to my sight. The picture upon it represents Noah’s Ark riding upon the waters of the Deluge. Underneath the picture of the ark is printed the command given by God to Noah to enter the ark :

“Cometh thou and all thine houses into the ark,” Gen. 7 : 1.

Noah is represented as standing on the front of the ark, sending forth the dove to see if it could find land, the story of which is beautifully told in the following lines:

“The dove set free from Noah’s hand,

Wandered a weary space,

But could not find the solid land

Or gain a resting place.

‘Tis thus the soul that strays from God,

No comfort can obtain,

‘Till it return to its abode

And finds the Ark again.”

I do not know what then prompted my young mind to choose this card, but now its picture and its lines have to my mind a deep significance.

*Note: The chum is Dr. Edward Ely, 1827-1858, who served as consul in Bombay under President Polk. (Battle Vol.3 p.814)