A few months ago my grandfather decided to a do a little spring cleaning. There was a storage unit in our barn that hadn’t been touched in years, full of mildewy furniture and worthless miscellany. He came across a metal container full of maps, mostly showing local topography and zoning. My aunt suggested that I might want them, so they escaped the trash heap.

When I got down to the barn I found a pile of mostly junk, covered in a plastic tarp because we were expecting rain. I found a few items worth keeping: the sled my great-grandmother had when she was a little girl growing up in Battle Creek, Michigan, a wooden tricycle that belonged to my grandfather, and a few plastic trucks for my son to play with. I found the box of maps and popped open the latch, and immediately knew that the contents were far more important than my grandfather had realized.

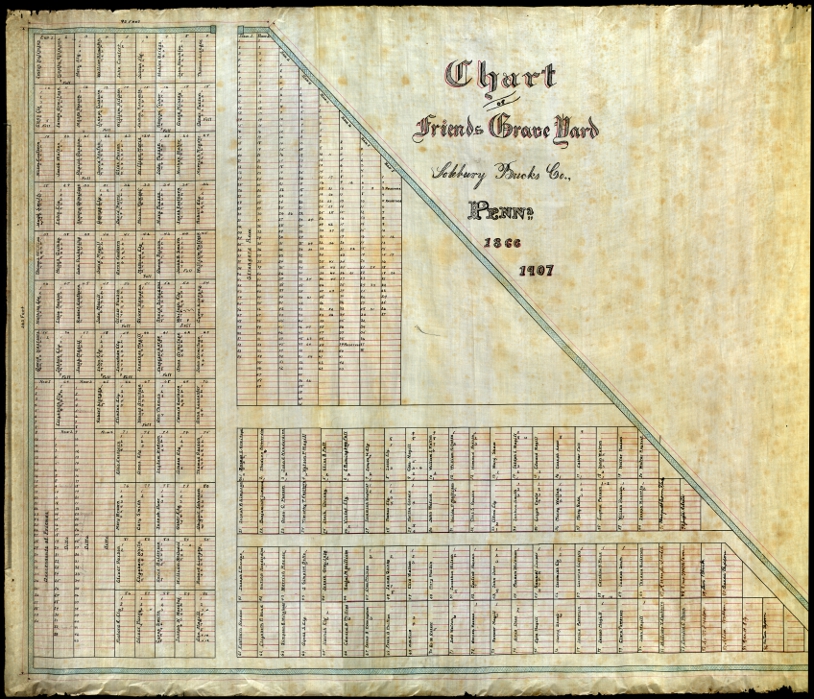

There were dozens of maps, but among the rolls of paper I recognized a draft of the map my great-grandfather made for the Solebury Friends Meeting burial ground in the 1960s. Then I noticed another roll that was clearly a much older material. With the box sitting in the gravel driveway, I rolled the map out a few inches and discovered that it was in fact two maps rolled together.

The first was from 1907.

The second was from 1866.

They were the original maps that by great-grandfather used as a reference for the modern map, and they’d been sitting in our barn for decades, totally forgotten.

I called the person currently in charge of the graveyard to tell him about my find and offered to bring it to the Friends Historical Library at Swarthmore College to deposit it with the rest of the Meeting’s original records, and I held on to them for a few months until I had time to make the trip.

A couple weeks ago I finally I finally had a day off, and decided to bring the maps to Swarthmore. My timing was fortuitous. That Monday I led a graveyard tour at Plumstead Friends Meeting. We assembled in the meetinghouse, and as I led the group outside towards the burial ground, a woman approached me with a box of documents about the meeting. At the time I was too focused on the tour to discuss it, and suggested that she talk to the clerk of the meeting. The next day, however, I was consumed by curiosity. I already had plans to go down the the Friends Historical Library that week, and thought I might be able to bring those papers as well. Luckily I ran into her in Doylestown a couple days later and proposed that I take them for her. She agreed.

When she dropped the documents off the next day, she brought a lot more than the Plumstead material. She also brought a collection of documents from Buckingham Meeting, and there was so much that it took her two trips to unload it from her car.

The Plumstead material turned out to be the notes and research prepared for a pamphlet published for the meeting’s 225th anniversary celebration on 1953, as well as notes about the ceremony itself. There were also two large photographs that were used in the pamphlet, one from c.1875, and one from 1953.

The Buckingham material was rather varied. One box contained about a dozen copies of the book published for Buckingham Meeting’s 225th anniversary in 1923, as well as a block print of the meetinghouse that was used for that book. There was a folder with newspaper clippings and other 20th Century material. Finally, there was a cardboard box that had been saved from Buckingham Meeting by the woman’s father. At some point a few decades ago, the members of Buckingham meeting had decided to indiscriminately “clean” their attic, and this box was a subject of the purge. Like the burial map from Solebury, these documents were almost destroyed.

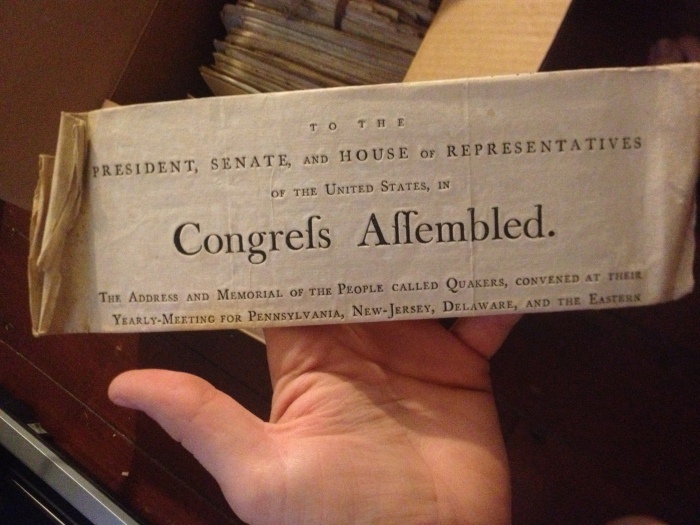

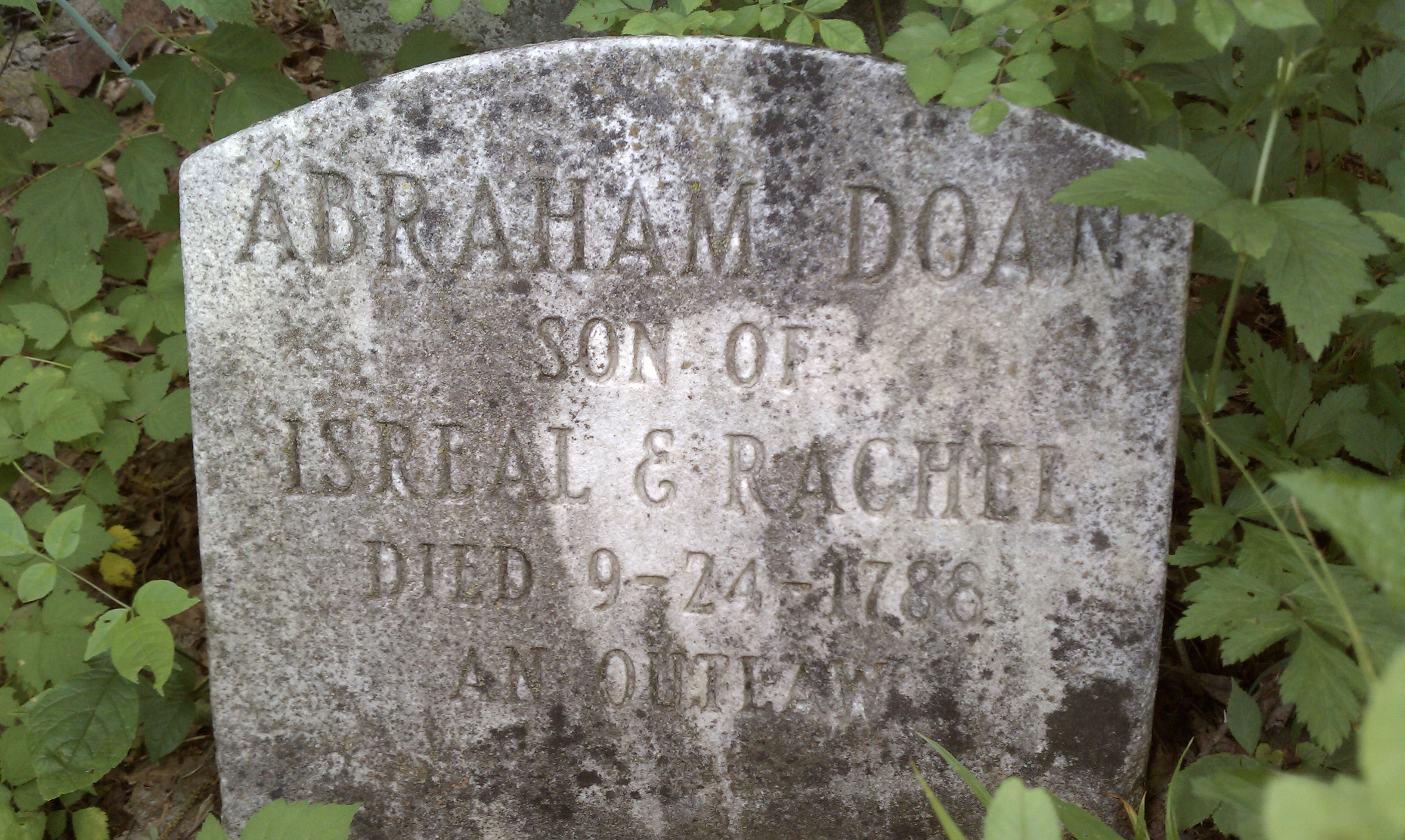

When I opened this final box I got goosebumps. I could tell by looking at the parchment that they were old. Really old. Most of them were tied together with string into little bundles, with a few groupings of loose papers between them. I saw the date “1776” peeking out from one of the bundles. When I brought them home and examined them further I found that some documents dated back to the beginning of the 1700s, and in addition to material from Buckingham, a lot of the documents actually came from Middletown Monthly Meeting. Most of them were excerpts from annual conference of Philadelphia Yearly Meeting, and epistles from the yearly meetings in London and Philadelphia. Some were testimony against members of meeting, or letters from people willingly leaving the Society of Friends. There were a few more recent documents that dealt with the Civil War. Perhaps the most interesting document is a letter written from a Quaker aid mission during the British occupation of Boston. She had kept them in storage for years, hoping to eventually deposit them in the archive, and I was finally able to bring them for her.

For the sake of brevity, I will show the individual documents in separate posts:

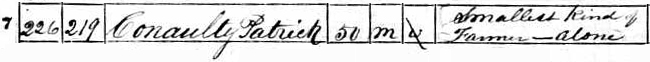

He was an Irish immigrant living on his own with no wife and no family. The enumerator manifests his pity for Mr. Conaulty in the “occupation” column, recording that he is not just a farmer, but the smallest kind of farmer–alone.

He was an Irish immigrant living on his own with no wife and no family. The enumerator manifests his pity for Mr. Conaulty in the “occupation” column, recording that he is not just a farmer, but the smallest kind of farmer–alone.