A man sharpens a cradle scythe, similar to Joseph Blundin’s murder weapon.

Today a house sits on the southern corner of Court & East Streets, as nice and unremarkable as any other house in Doylestown. Few would guess that 177 years ago a murderer was buried here. Even fewer would guess that 157 years ago they dug him back up.

This is the story of the executed murderer Joseph Blundin and Doylestown’s forgotten burial ground.

A Crime of Passion

Joseph Blundin was a farmhand with a young family at the time of the crime. He appears on the 1830 US Census living in Bristol with his wife, both in their 20’s, and three children, all under 5 years old. The account of the crime and the public support for Blundin in its aftermath paint him as normal man driven by his circumstances to commit a horrendous act.

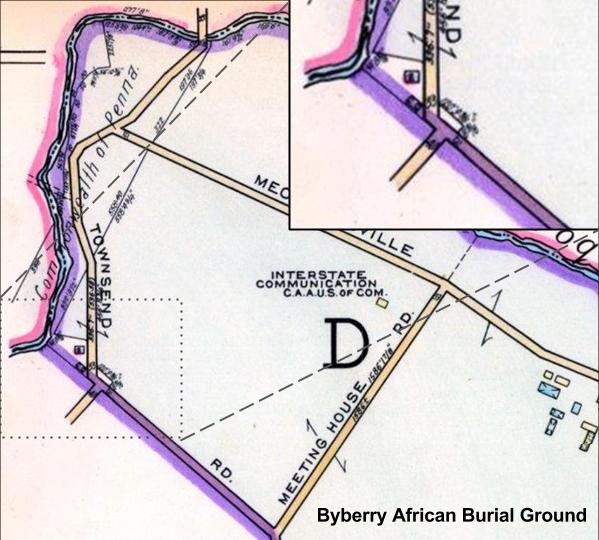

The murderer and victim were harvesting oats on the farm of Samuel Headly, probably the S. Headly marked with a red “X” on this map from 1857. The murder occurred somewhere on the road from Headly’s farm to Bristol.

On the day of the crime Joseph Blundin and his victim, Aaron Cuttlehow, were working together harvesting oats on the farm of Samuel Headly near Bristol. J.H. Battle recounts the details of the crime as revealed during the trial:

The prisoner and deceased were at work on Sunday, July 27th [1834], with other men, five or six, engaged in cradling oats. At dinner one of the hands ran out of doors with a pie, deceased and the prisoner chasing him. In their playfulness a shoe was thrown which hit the prisoner. Shortly afterward the deceased came into the house crying, and said the prisoner had hit him on the head with a stone. This disturbance was settled, and they all went to the field to cradle oats. When nearly done a quarrel arose between the prisoner and the deceased, and the prisoner was thrown down and received several blows from [the] deceased in the face. The deceased with another then helped him upon his feet, and his knees giving way under him, they assisted him up a second time. The prisoner then took his cradle and started for home. He was asked to ride twice, but refused, and said, angrily, he would walk. From fifteen minutes to half an hour later he was overtaken by the wagon, walking slowly. He was asked to get up and ride. The prisoner made no reply, but raised his cradle from his shoulder and struck at the deceased hitting the cradle of the deceased, which he raised to guard the blow; the deceased at the same time losing his cradle from his hand, which fell upon the ground. The deceased (Cuttlehow) then sprang from the wagon to make his escape, but stumbled and fell as he reached the ground. When he had crawled a few paces the prisoner came upon him with his cradle uplifted and struck the scythe through the neck of Cuttlehow. The latter cried, “Take it out, take it out!” sank on the ground and died in one or two minutes. Some one said to the prisoner: “He will die,” who replied: “Let him die.” Liquor had been used in the field, but there was no satisfactory evidence that the prisoner was intoxicated. The jury was out eleven or twelve hours, and returned a verdict of murder in the first degree.

We don’t know who started the fight, but it’s clear that the dead man had seriously beaten Blundin in the earlier scuffle, and that Blundin was emotionally distressed by the fight. Instead of escalating the conflict he attempted to walk home alone, only to be confronted again. After being pushed one last time by the other farmhands, he lashed out and killed Cuttlehow with the tool he happened to be carrying. All of this evidence portrays the crime as a temporary lapse by an otherwise decent man rather than the premeditated work of a cold-blooded killer.

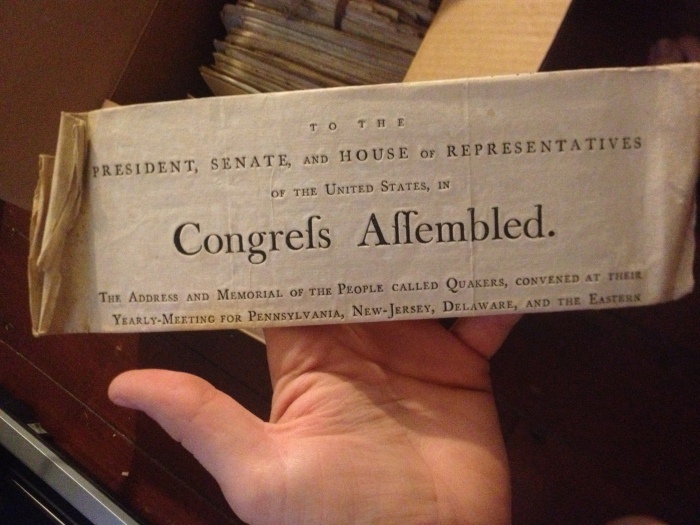

After he was sentenced to die by hanging, the public rose up in support of him. While the facts of the crime were not disputed, the death sentence issued seemed harsh and unnecessary. Battle reports that even Charles E. DuBois, the Deputy Attorney-General for the Commonwealth, “was overcome with emotion in reading the indictment to the unfortunate man.” The citizens of Bucks County appealed to the government for mercy, petitioning the Governor Goerge Wolfe and both houses of the State Assembly in an attempt to have his sentence commuted to life in prison. They attempted to save Blundin through multiple avenues, begging for the Governor and legislature to take action in his case specifically as well as attempting to change the state laws regarding criminal sentencing by giving the governor the power to commute death sentences to life in prison or by abolishing the death penalty altogether.

The general thrust of their appeals can be seen in the debate that took place on the floor of the Pennsylvania House of Representatives, where a representative named Harrison introduced an amendment:

…in accordance with the wishes of a large number of constituents; men of the highest respectability who believed, and honestly believed what is set forth in petition to the legislature, that at the time Joseph Bliindin committed the act for which he has been sentenced to death, he was not in a sound state of mind. The unfortunate individual was born and brought up in his vicinity; he has a family consisting of a wife and several children, and a general feeling pervades that community, that he should become the object of legislative mercy. In addition to these wishes in of Joseph Blundin, a general feeling was manifested in favour of the abolishment of capital punishment in all cases…

Unfortunately, Blundin’s supporters failed in their attempts. Those opposed to the measures claimed that any action in his case was unconstitutional, either by violating the separation of powers or because such a law would affect one man instead of all people under their jurisdiction. Finally, after multiple stays of execution, Blundin was scheduled to die on Friday, August 14th, 1835 between noon and 3pm.

Blundin made one final attempt to save his own life by escaping from the Doylestown jail. Battle describes the failed escape as follows:

On a Sunday in May Blundin attempted to make his escape from the jail. He managed to cut off the rivets of his hopples, burn a hole through the floor, and, after gaining the jail yard attempted by means of a rope formed of his bedding, to scale the outer wall. The fastenings gave way when the prisoner was near the top and he fell to the ground, where he lay in a bruised and helpless condition until found in the morning by the sheriff. Such was the sympathy of the public that a rumor that the sheriff left the means of escape within reach of the prisoner and then left the building to give him an opportunity to use them, obtained general credence and no marked disapproval. The unfortunate man was carried back to his cell and on the day appointed by the governor’s last respite was executed in the yard of the jail. The prisoner was unable to stand on account of his injuries, but he met his fate with resignation and courage.

Then, by way of the gallows, Joseph Blundin found his temporary resting place in the now forgotten potter’s field.

The Doylestown Potter’s Field

In the first half of the 19th century this plot of land was the county potter’s field, a burial place of last resort for the indigent and a site to inter the unclaimed bodies of strangers and prisoners. Very little is recorded of the Doylestown potter’s field. Like the almshouse, the courthouse, and the county jail, the potter’s field probably came into being around the time that the county seat moved from Newtown to Doylestown in 1812. I could only find the potter’s field on one map, W.E. Morris’ 1850 atlas of Bucks County:

The only mention of those buried here comes from W.W.H. Davis’ History of Bucks County, Volume II:

The old “potter’s field,” where several persons were buried, including one Blundin, of Bensalem [actually Bristol], hanged for murder about 1838, at the corner of Court and East streets was sold several years ago by authority of an act of Assembly and now belongs to a private owner.

I was able to act of Assembly that Davis mentions. Passed on May 7th, 1855, the act instructs Bucks County to remove the bodies and sell the land, stating:

…it shall be the duty of the commissioners of the county of Bucks… to remove or cause to be removed to the burial ground of the Bucks county almshouse, the remains of all persons now interred in the public burial ground, situate at the corner of Court street and East street, in the borough of Doylestown, and known as Potter’s Field, and that the same shall no longer be used as a place of burial.

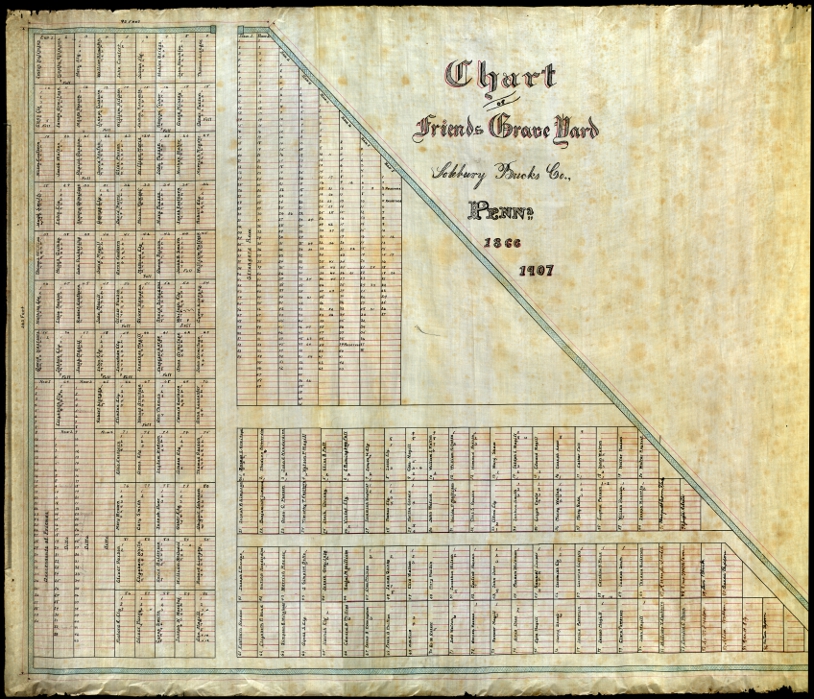

The almshouse opened in the spring of 1810, and the first inmate to die there was a black woman named Dinah, allegedly 115 years old. According to almshouse records (List of Paupers in the Almshouse 1810-1833, p.31, available on microfilm at the Spruance Library), Dinah died on April 20th, 1810, and the almshouse supplied her with a “cape shirt hankercheif and coffin” for her burial. While I haven’t been able to find any information about the almshouse burial ground, it preceded the Doylestown potter’s field by at least a couple years and was probably used concurrently.

At some point, the almshouse stopped using their own burial ground and began interring inmates at Doylestown Cemetery. I talked to Kat Landis, whose family oversees cemetery, and she said that the back row of the cemetery was laid out as a “Strangers Row” with inexpensive plots. According to her, this area became the burial ground for inmates from the almshouse, prisoners from the county jail, and people who died at the Doylestown hospital. This “back row” is now in the center of the cemetery near the main gate, since Hope Cemetery was added next to Doylestown Cemetery and the two were later unified. My guess is that when these cheap plots became available there was no more need for a government maintained burial ground. I have found some written evidence of this in the Almshouse and Hospital Register 1872-1889, which reports that inmate Henry Puff was buried at Doylestown Cemetary on the November 29th, 1883.

Doylestown Cemetery was founded in 1849, and probably wasn’t in operation yet when the 1850 map was made. By 1857, however, the cemetery is presented in the atlas published by Khun & Shrope. You can see that the Dolyestown Cemetery has been added to the map, but the potter’s field is gone:

Whether Joseph Blundin and the others buried in the potter’s field were actually disinterred may be up for debate. The graves in potter’s fields are usually unmarked, and the success of disinterment would depend on how systematically the graves were laid out and how well the locations were recorded. I’m sure they made their best effort to clear the land of bodies before selling it to a private owner, but after 20 years in the ground did the county remember the location of Blundin’s grave? He probably lies on the almshouse grounds, but every time I pass the old potter’s field I wonder if any graves remain.

(The house now standing on the potter’s field.)