(Click on any portrait to see the extremely detailed hi-res scan)

I purchased this collection of photographs a few months ago. In addition to the fact that they’re interesting photographs covering a wide span of time and including diverse photographic processes, I was primarily motivated to buy them because they came from Bucks County and the subjects were named. With a little research I was able to find out who they were and where they came were from.

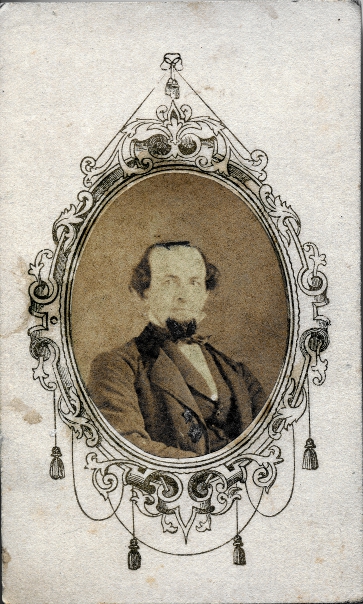

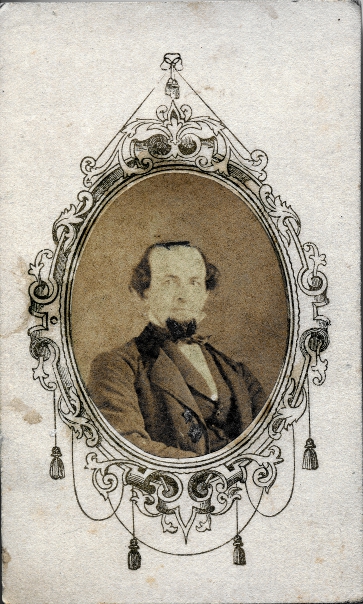

The oldest is that of David Kerbaugh, a salted paper print that probably dates to before 1855. Kerbaugh was born in 1817 in Warrington Township, Bucks County. His father Justus later moved the family to Horsham, Montgomery County. He died in 1867 and was probably buried at Horsham Friends Meeting, where is wife and other members of the Kerbaugh family are buried.

When fully zoomed in you can see the rough fibers characteristic of salted paper prints.

The next oldest are the portraits of his brother-in-law, George Palmer, and his daughter, Mary “Minnie” Augusta Kerbaugh. These are both ambrotypes, photographs made by pouring a liquid emulsion on a plate of glass. They’re the earlier style of ambrotype, in the photograph is taken on clear glass and black varnish is then painted on the back in order to make it a positive image. They date to about 1860.

The photographer hand-tinted his lips and cheeks.

The portrait of George Palmer is very small, a 1/16th plate measuring less than 2″, housed in a broken Union case made of hard plastic. The photo of Minnie Kerbaugh has clearly been altered. The metal frame holding the pane of glass is warped from being opened, and it is slightly too large for the leather case. It looks like the glass cover may have broken and been replaced with thicker glass that doesn’t fit correctly in the metal frame.

Notice the red tinting on her cheeks and the green tinting on the shoulder of her dress.

Minnie remained single into her 50s, when she married Alexander Forbes Porter Jr., a widower who had employed her as a housekeeper for over a decade before their marriage. Porter spent most of his life in Philadelphia before moving to Langhorne.

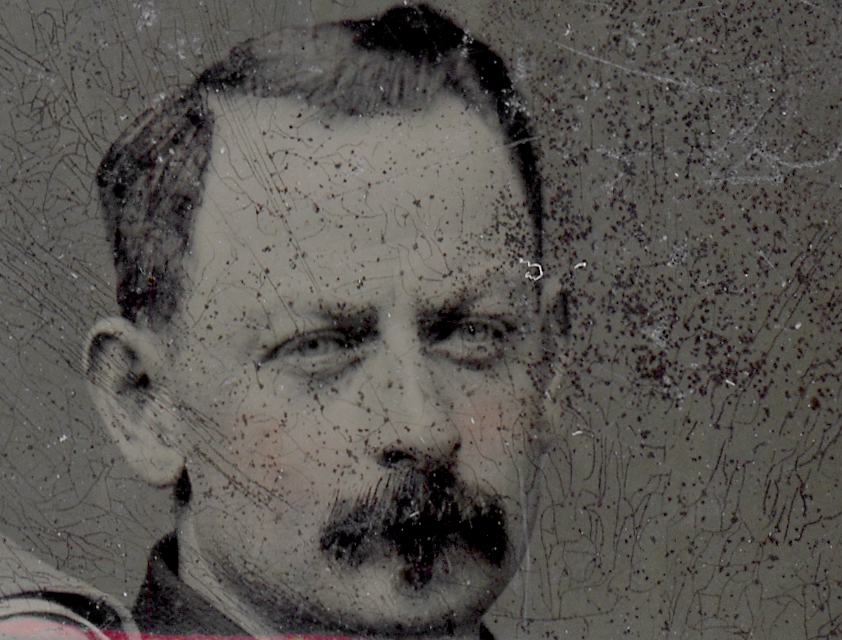

The collection also contains an opalotype, a rare early form a photography created by pouring emulsion over white opaque glass. Unfortunately, it’s the only one that hasn’t been identified. Based on the family resemblance, the man is probably a Porter. It may be Alexander as a young man.

This opalotype was extremely faded before I touched it up. It was difficult to view at most angles. Also known as opalypes or milk glass positives, these photographs are made by pouring collodion emulsion on opaque white glass.

After adjusting the levels and hue concentration, the subject is easier to see, as is the hand-tinted bow tie. The pigment on his chin was smudged, demonstrating how fragile the unprotected emulsion is. Zoom in to see the particles of pigment on the surface of the glass.

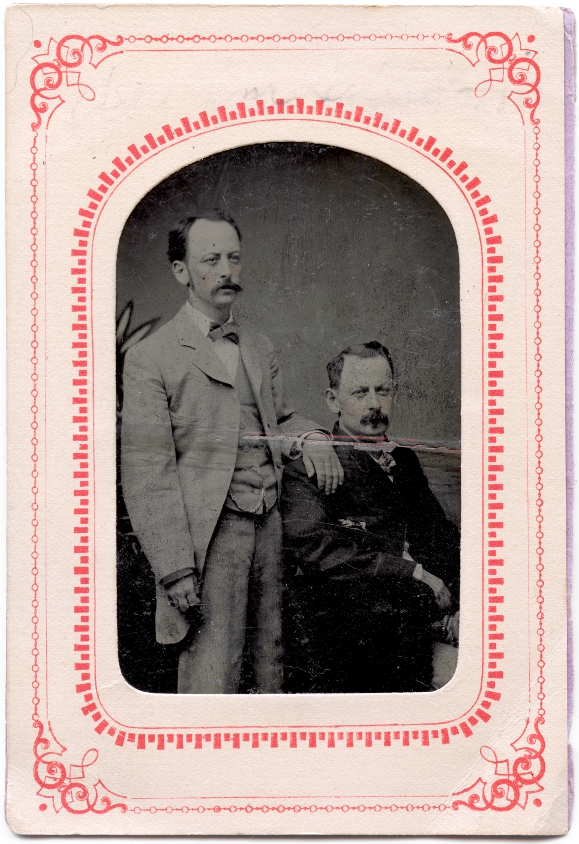

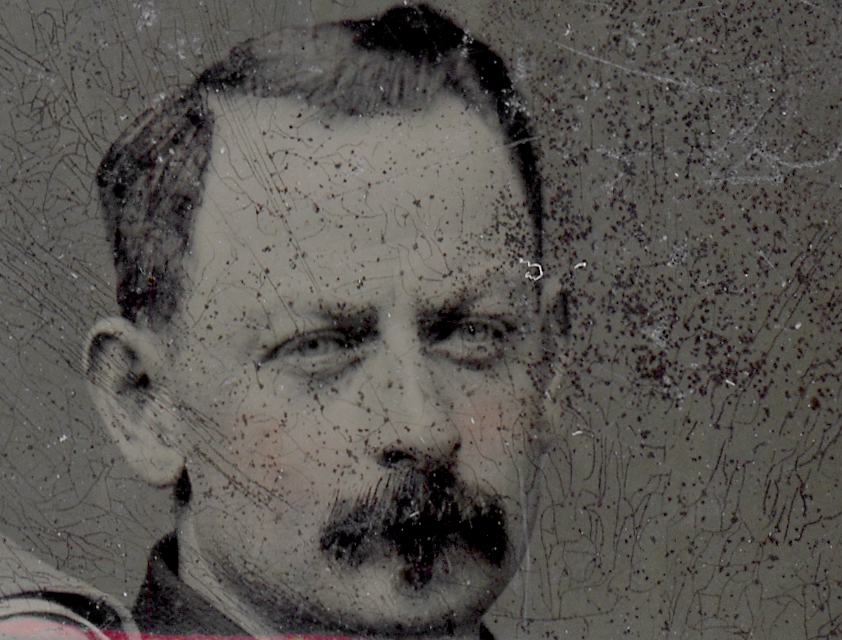

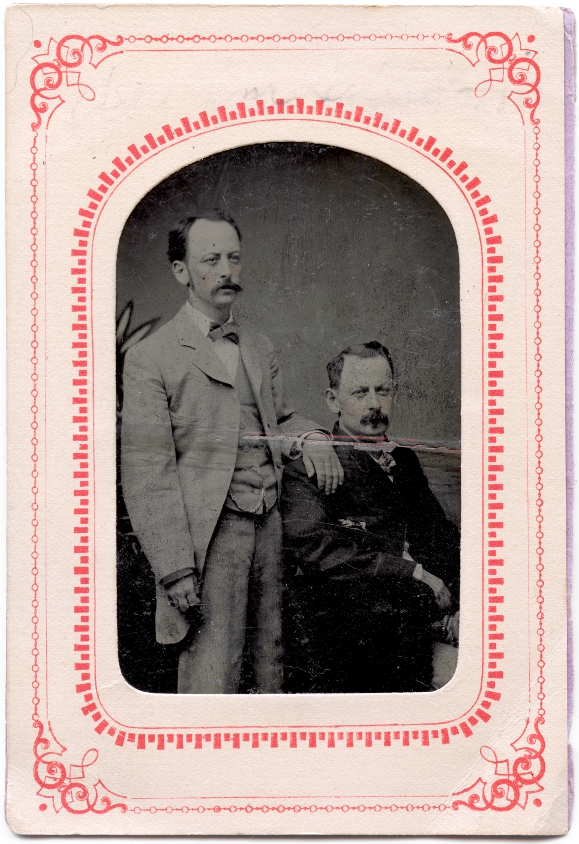

There are two other photos of Alexander, both tintypes, photos made by pouring a liquid emulsion on a piece of metal. The first shows Alexander (right) and his brother Richard (left), taken in Philadelphia on August 30th, 1892. This photo is still in its decorative paper sleeve. While early tintypes were housed in cases like daguerreotypes and ambrotypes, they were more often displayed in paper sleeves or specially designed books. Matting the image behind paper hides the irregular shape of the plate as well as the edge of the photo where the emulsion is uneven.

Notice the line below Alexander’s head where a swath off emulsion is gone, exposing the iron plate below. This sort of damage usually occurs when a tintype is bent, causing the inflexible emulsion to break and fall off.

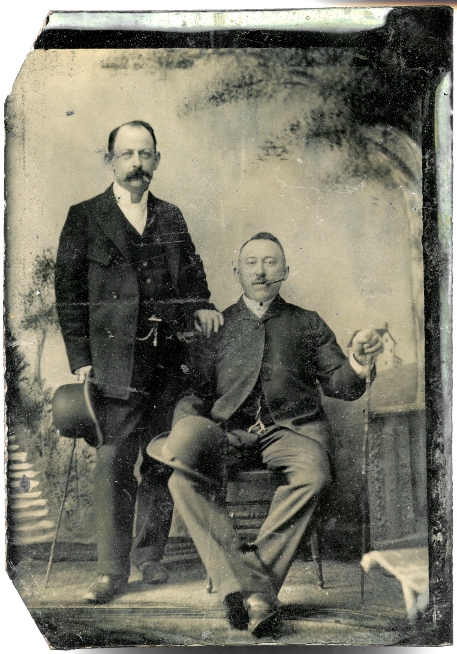

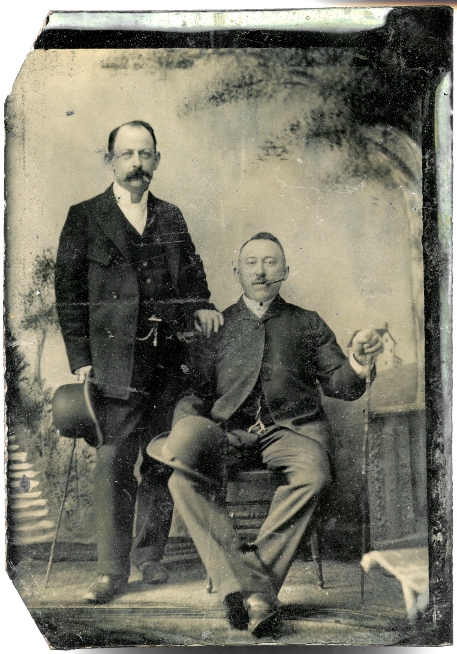

The other photo shows Alexander standing with an unnamed man. Alexander looks a good bit older in this photo, having gained some weight and lost some hair. Based on these features, this photo may date to around 1900-1910.

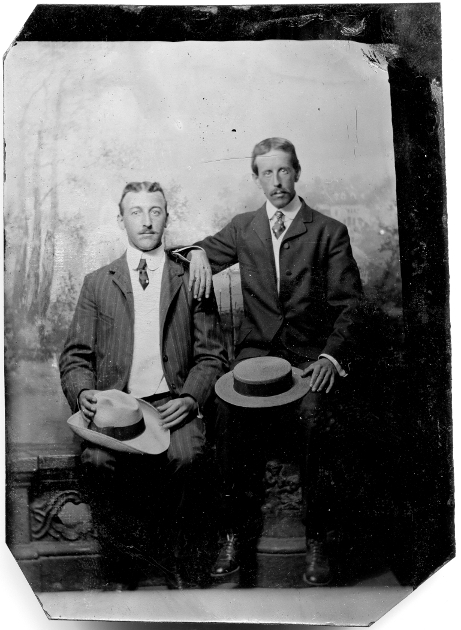

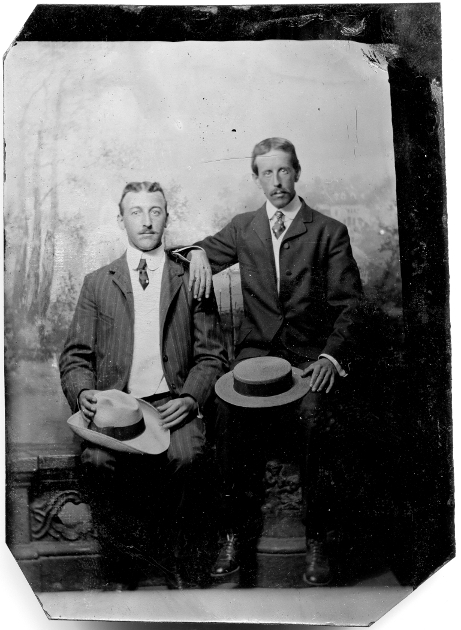

The last photo, also a tintype, shows Alexander’s son-in-law Clarence Luther Green. Born in Shippensbury in 1877, Clarence moved to Philadelphia where he married Lillian May Porter, Alexander’s daughter from his first marriage. The couple eventually moved to Langhorne. Clarence is seated on the left, and his friend Linford Logan is on the right. The photo was taken on August 31st, 1902.

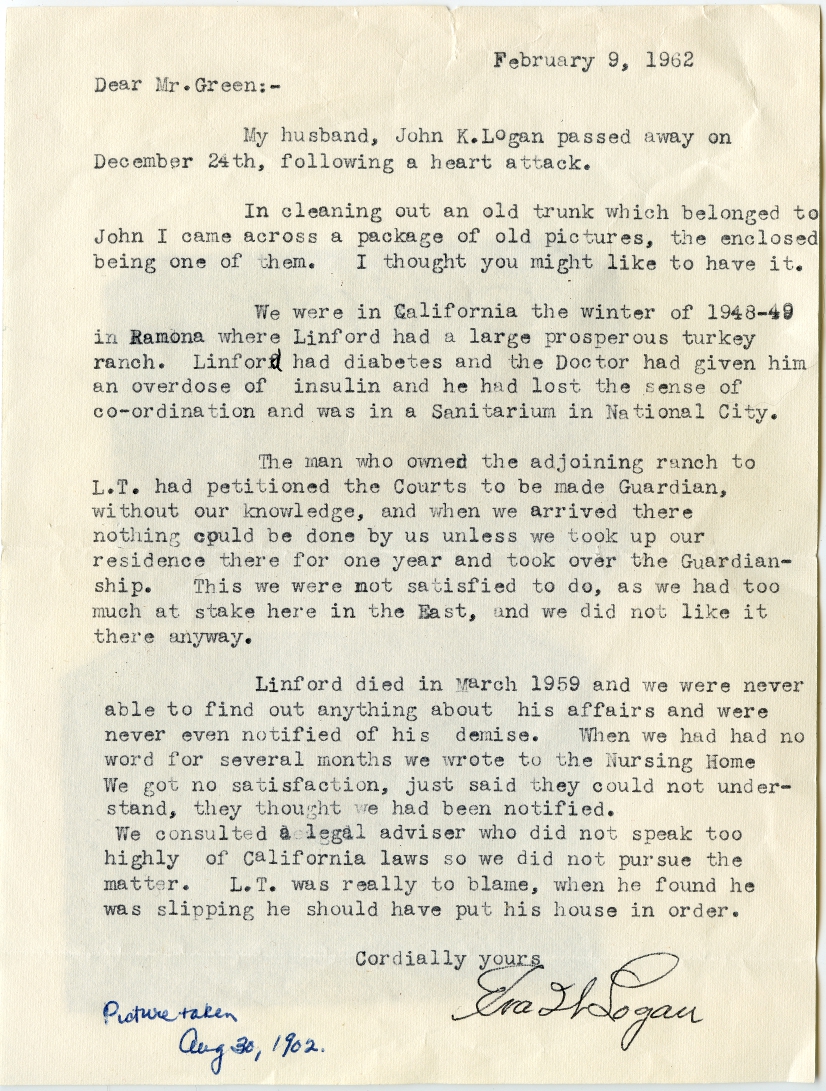

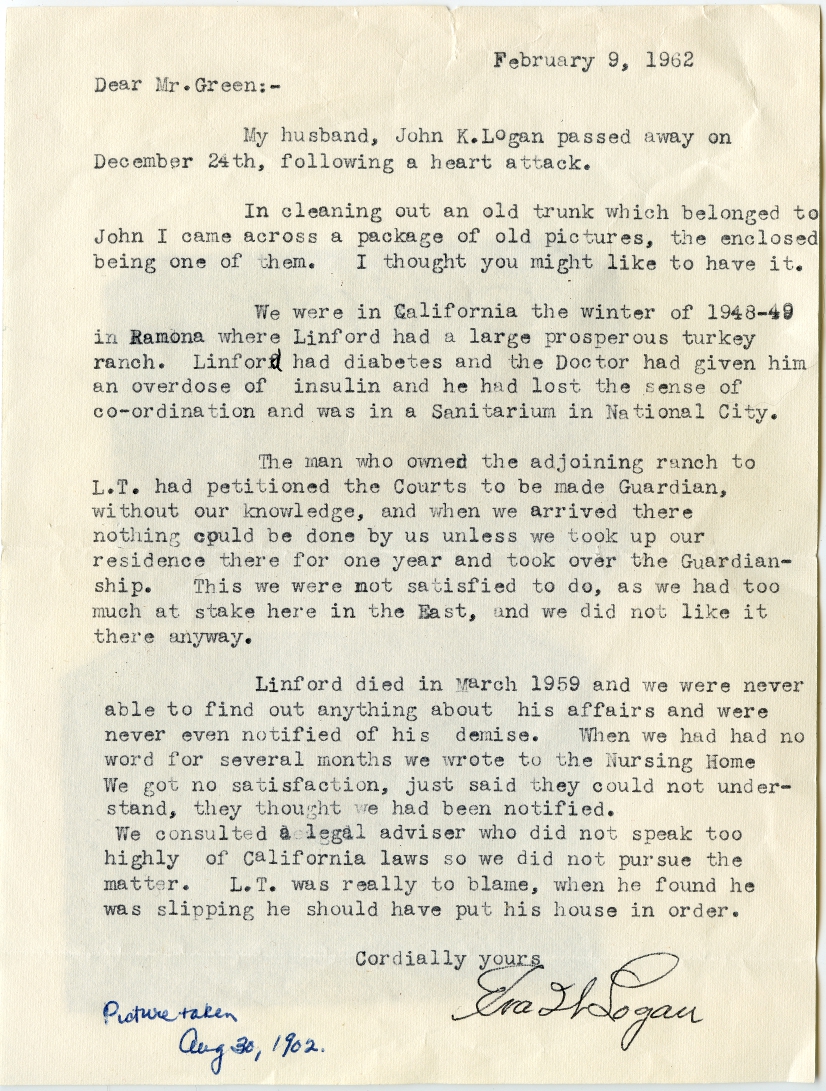

When I purchased the collection of photographs, it contained the following letter:

John K. Logan was Linford’s brother. They grew up in Horsham, Montgomery County, before Linfored moved to west. John stayed in the area and lived in Lower Moreland until his death in 1961. He and Eva are buried in William Penn Cemetery.

It’s not clear which Mr. Green the letter is addressed to. Clarence was still alive, but a very old man. It may have been addressed to his son, Emerson P. Green.

It’s likely that this collection of photos was owned by Emerson. The note accompanying one photo of Alexander Porter refers to him as the grandfather of Emerson Green, indicating that they may have been identified for Emerson by an older relative. Emerson had no siblings and no children, so it makes sense that he would have been the last owner.

Emerson Porter Green died just last year on October 23rd, 2012, at the age of 97. His wife, Jean Mitchell Green, died this January. I bought these photos on eBay in March, so perhaps the seller bought the photos at their estate sale. Regardless, after being kept in the family for 150 years, they were sold a stranger. Usually a collection like this would be parted out and sold as individual pieces for more money. When family photographs are transformed into commodities they are stripped of their context and the identities of their subjects are usually lost. According to Emerson’s obituary, “He spent a large amount of his time volunteering at the Langhorne Historical Society where he was involved in archiving historical artifacts for the society.”

Given Emerson’s dedication to preserving local history, I’m glad that I was able to purchase them and save them from that nameless abyss.

Emerson and Jean Green are buried at Middletown Friends Meeting.