Strangers Row, an open patch of lawn

When I read Rayna’s post about an unknown grave at Solebury Friends Meeting, the text of its headstone obscured by tree roots, I immediately knew the grave she was talking about. I grew up in that graveyard.

We were the caretakers, and when my mother worked my brother and I went with her. We spent hours upon hours in the cemetery, finding ways to keep ourselves occupied. One of our favorite games was to jump from headstone to headstone, moving up and down the rows while our mother mowed. I’ve read every name on every headstone, connecting the roads and hills of Solebury to the old family plots (Ely, Paxon, Armitage, Kitchen, Pidcock, Magill). As a teenager I even dug some graves myself. I know the place pretty well.

But this enigmatic tree-eaten grave gave me pause. Weren’t there other unknown graves? A fragment of a memory came back to me. Something about a man found dead in a tree. A stranger whose body was discovered and buried in the graveyard. I thought I’d read it somewhere, so I looked through some books (MacReynolds’ Place Names in Bucks County, Davis’ History of Bucks County) but found nothing.

So I asked my father, who was the caretaker for about ten years starting in the mid-70s until my parents divorced. Did he remember anything about unknown bodies buried in the graveyard?

He came up with the same story about a stranger found dead in a tree (We can rule out the power of suggestion. I hadn’t mentioned it). The details were foggy, but these fractured shards emerged:

- He thinks the tree stood on the left near the wall as you enter the graveyard from the meetinghouse, but it was no longer standing when he became caretaker.

- If it wasn’t a tree in the graveyard, it was definitely a tree somewhere on the meetinghouse grounds.

- The body was in the branches of the tree, not hanged.

- He thinks Rachel Franck, a member of Meeting that lived just south of the graveyard, used to mention the man in the tree occasionally.

- He was buried in Strangers Row.

This last detail caught me by surprise. I spent the first seventeen years of my life in that graveyard, but I’d never heard of Strangers Row.

They were not all strangers, he explained. That’s where they buried non-Quakers, across the lane from the oldest section of the graveyard (Perhaps called “strangers” to distinguish them from Friends?). Most of them were known members of the community, they just weren’t members of Meeting. However, he said that there were more graves whose occupants were in fact unknown.

At this point I reached the limit of my tolerance for half-remembered ambiguities, and I decided to find some documentary evidence. I tracked down a list of graves on Interment.net (provided, I should mention, by my grandfather who has been in charge of the graveyard for decades) and found some promising leads. Of the 21 “Unknowns” two stuck out:

- d. 10/28/1880, stranger found dead, Sect. B-6-4

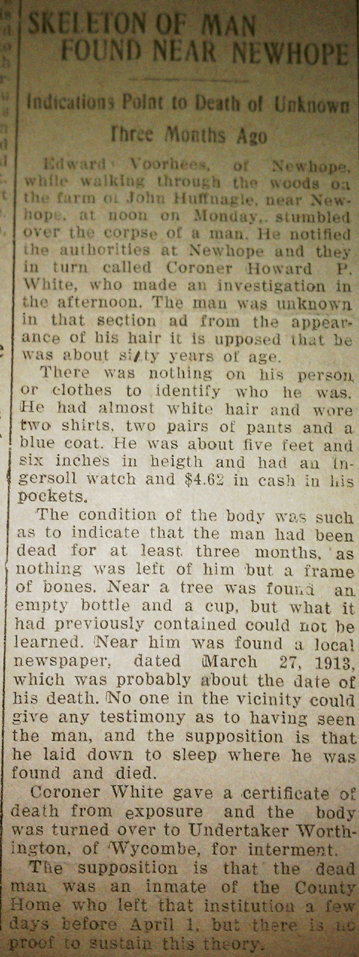

- d. 7/21/1913, man found in woods, Sect. B-9-13

Could one of these be the man found dead in a tree? I headed to the graveyard to investigate.

Strangers Row

I came looking for a row of headstones, but what I found challenged a basic principle of my mental geography of the graveyard. Strangers Row was empty. My whole live I assumed that every grave had a headstone, but this open patch of lawn was full of graves, unmarked and unknown.

Headstones are expensive, and even today new graves might be marked with temporary tags for years before a proper stone is installed (In this section I actually found a weathered plastic grave tag for Oscar Carter, deceased 1904). Whether they lacked the family ties or money, these strangers’ graves were left without a permanent mark.

Analyzing the list of the dead, I made a startling discovery. It seemed like a disproportionate number of the dead in Strangers Row were children.

I started counting.

In the first three rows, 74 of the graves are specifically listed as children, while only 67 are not. I doubt this can be explained by higher child mortality rates alone. A more likely explanation is that these children belonged to families who were not permanent residents of the community. Sometime after the children died, the families moved on and were buried elsewhere. Furthermore, many of the adults buried had unique surnames, indicating that they were not related by birth or marriage to the members of Solebury Friends Meeting. To further complicate things, one plot (d. 6/7/1886, baby from home in Philadelphia) suggests that perhaps the meeting took some bodies in for charity.

Four Unknowns

I now knew that to find my buried strangers I’d have to identify unmarked graves. I would have to triangulate their location by referencing graves with legible names. I loaded the Interment.net grave listing on my Android phone and went about identifying headstones close to the unmarked graves, narrowing in on my target by the row and plot number. In a few minutes, I found the graves of my two best leads:

Stranger Found Dead 1880

Man Found Dead in Woods 1913

Does one of these graves belong to the man found dead in a tree? Was the story my father and I remembered a corrupted retelling of a man simply found in the woods in 1913? Or was he one of the other unknowns, listed only as a question mark on the record of graves? My father and grandfather had no further information. Maybe some other old timer at Meeting knows the answer. For now, my leads have gone cold.

While I was at it, I also looked up two more intriguing unknowns, listed as “Irish Woman” and “Boy Drowned in Canal”:

Irish Woman and Boy Drowned in Canal

How did these two come to rest at Solebury Friends Meeting? No dates are provided. The first stone between them belongs to William Fennell, also undated. The other two Fennells were buried in 1871 and 1881, so it’s reasonable to guess that William died around the late 1800’s. The rest of the plots surrounding them are also undated, and almost all belong to children. Of these children, four have parents buried here, and those parents’ dates of death range from 1867 to 1906. This places the children’s deaths in the mid- to late 1800’s.

What events brought them here? Why were they identified only by ethnicity and manner of demise? For now these reticent strangers will keep their secrets.

I’ll leave you with one of my favorite headstones, belonging to their fellow cemetery residents, 24-year-old Austin H. Cowdrick (d.12/6/1881):

“Unceasingly floweth the cold cold tide, of Death’s dark and lonly [sic] river.

And he whom the Boatman carrieth o’er Returneth oh never never.”